A few years back I was at a panel discussion at MoMA that featured, among others, the artist Kerry James Marshall. Kerry is a lively speaker, candid and very engaging, aside from being a major artist with a great deal of wisdom to impart. At some point in the conversation, he was speaking about how artists should engage with the art establishment, arguing that mere confrontation is not always productive. He started articulating how, in his own work, he was able to pursue his vision while at the same time satisfy the demands of the powers that be. At that point a skeptical speaker in the panel asked him: “isn’t that the definition of academic art?” Laughter ensued, and Marshall immediately went back to contest that suggestion and try to clarify what he meant. But the question, which seemingly deflated Marshall’s carefully constructed argument, lingered— and it has continued to do so, at least in my mind.

In case it is not obvious, “academic” in the context of that conversation does not refer to the aesthetic of the French academy of the 1860s, but to the idea that a successful and recognized contemporary artist, in the process of becoming mainstream, can becoming formulaic, no longer radical, path-breaking, or iconoclastic. Becoming academic in this sense means, at best, resting on one’s laurels, and at worst, turning into a has-been— which is why it is not a nice insinuation to hear about one’s work.

It is well-known that, particularly as we reach maturity, we all think of ourselves younger than we are. Certainly as the cliché dictates age is greatly dependent on attitude, but even then, set reference experiences that we see as our extended present reality (for example, in the case of art, important exhibitions, artworks or events experienced several years ago, particularly those when one was at their prime) are merely history for younger people, and so we become history to them as well. There is thus an increasing dissonance between our own perception of the present and the perceptions of others of us as a living vestige of the past.

Another way to put it is that every artist has an image of oneself in the back of their mind; as we age, the mental image remains largely the same. It is, in a way, like an inverse version of a Dorian Gray portrait.

Oscar Wilde’s famous 1890 short story about a young and beautiful man who sells his soul to the devil so that a portrait of his absorbs the indignities of aging while he remains untouched by time, can be read as a parable about the projections we make onto art and how the readings we make onto artworks become, in a way, a symbolic load that we place onto the object. The fact that the painting, in the story, absorbs the aging process of the young man makes the object a redeemer of sorts for Gray, a filter of evil and decay that keeps his body pure and untouched. It is a parable about art as deliverance, but with the ultimate message that this supposed deliverance is nothing but a fiction, a temporary distraction from the fact that nothing can prevent our own ultimate decay. But it can be read also, and to my point, as a story about our obstinate refusal to accept or perceive change.

To recap and clarify: becoming “academic” in art today, however, is more than just getting old: it is the. gradual process by which our radical and experimental ideas, which might have been transformative at a particular moment in the art, go the way of formulation, of recipes. Now that I recently joined actual academia and teach at the university level, I can see how the very structure of higher education, with its annual cycles and administrative structures, can easily lead to teaching by formulaic and standardized, homogeneous methods. In spite of the distinction we try to make between modern and contemporary art, the fact is that today now teach conceptual strategies in the same way in which we teach the Venetian painting method. In art school, the goal is to generate artists who will formulate new languages, but we mostly teach them dead languages.

Needless to say, like practically any other artist, and like Marshall himself, I have always been concerned about becoming “academic” (in the sense that I originally described). In fact, I have always been keenly aware of the blind spots of my age, whatever my age was at any given point; and in fact, self-referentiality was an obsession of mine even before I discovered art — while I have always been temperamentally old-fashioned, and too nostalgic for most normal people’s taste, it has been that obsession with meta (note: not Meta) before it was fashionable (although now meta will likely be going out of fashion as Generation Alpha displaces Generation Z). But because of that heightened awareness of my own subjectivity, and because I came of age during postmodernism, I have always felt aligned with those skeptics (not nihilists) who embrace change but with a certain inherent skepticism, knowing it will not last; knowing that this exciting new thing will also fade, knowing that the hidden Dorian Gray portrait is bearing the wrinkles. I then wondered: given the fact that all art goes down this path, why not embrace this process? Instead of naively believing that our works will be forever young, why not properly plan for, and even set, their own expiration date?

In 2010 I tried to first articulate this view in a text titled Alternative Time and Instant Audience, where I basically argued that if we want to be the worthy inheritors of the alternative, artist-run spaces such as the ones that emerged in the 1970s in New York we should focus more on experiential art and less on static exhibitions; in other words, to really consider the live (public) program itself as an alternative space. And I still believe that to be true. As to what concerns the inevitability of our own eventual “academization”, the fact that the Dorian Gray portrait is putrefying behind the curtain regardless of how we try to hide it, the best is to preemptively engineer of own end by creating projects with a set expiration date; instead of running things forever until they are the shadow of themselves. In other words, one might as well destroy the painting early on, before it is too late.

Around the time I wrote that essay I was particularly critical of the scholarly art symposiums I had to organize as part of my museum job —rigid, marathonic and overbuilt events that felt like fruitless rituals for the benefit of only a handful of people, aside from being interminable. What if, I thought, I were to organize a whole conference that lasted only one hour? I thought of the piece The Dogg's Troupe 15 Minute Hamlet, by Tom Stoppard, a 1978 humorous, abridged version of Shakespeare’s play that is performed in 13 minutes followed by a hyper-compressed version of the same play in only 2 minutes. In the 1990s I saw the puppet version of this play by the Croatian master director Zlatko Bourek —a comedic masterpiece— and I thought: if you can do Hamlet in 2 minutes, anything is possible.

In 2016, I was invited by the Czech curator Tereza Jindrová, who ran the public programs of the Jindřich Chalupecký Society in Prague, to propose an idea for this contemporary art center, focusing on the subject of socially engaged art. My proposal was The Mayfly Conference.

The Mayfly is an aquatic insect of the ephemeroptera order, part of an ancient group of insects known as palaeoptera. Known also as “one-day insects”, they are the animals with the shortest life span on earth. After they hatch and reach their adult form, most mayflies live only for 24 hours, while some adults can live only for 5 minutes.

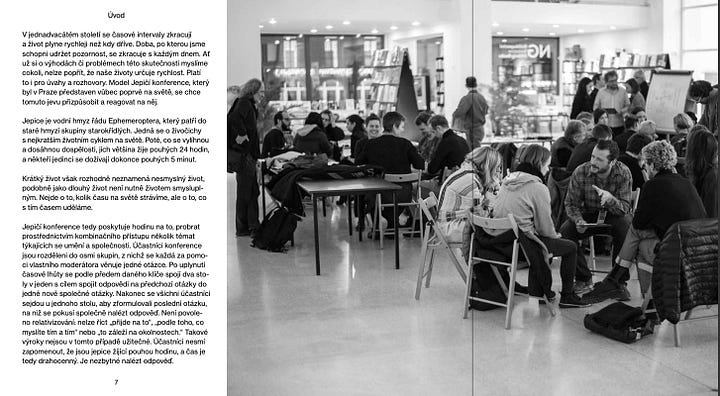

The Mayfly conference took place on a snowy December night in Prague. We had about 40 participants at the conference, structured for only one hour.

I picked a combinatory approach— a format with which I was experimenting a lot at the time, consisting in creating discussions that later would merge with one another to arrive at a single theme. Each table had one moderator and addressed a particular question. The whole event was a tribute of sorts to Ernest Gellner, a Czech-British philosopher who was an important exponent of critical rationalism, a philosophy that opposes over-reliance to language and is critical of aspects of logic. Our brief discussions sought to primarily think about the barriers that language imposes as an interpretive tool to art.

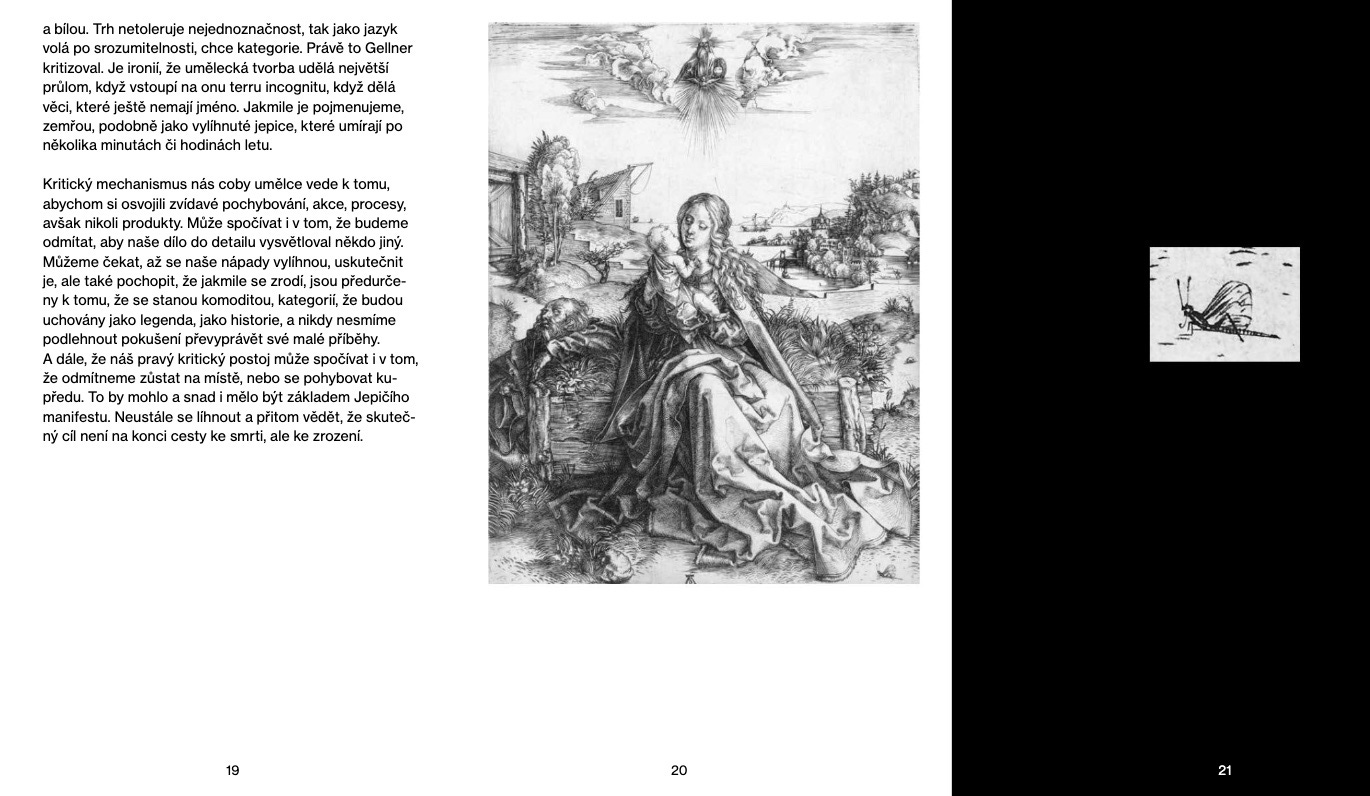

The whole event was a bit chaotic, dynamic, and very energetic, a Black Friday version of pedagogical performance art. An image that was used as an emblem of the entire evening was drawn from a 1495 engraving by Dürer, titled “The Holy Family with the Mayfly”, a depiction of the holy family next to a river or a lake, and on the lower right corner of the image an insect with all the characteristics of the mayfly. Dürer might have wanted to use the insect as a metaphor of heaven and earth, of the ephemerality of life, but primarily, I believe, of transformation, and perhaps, of the resurrection.

Looking back to that night in Prague, and thinking about that conversation about academization with Kerry James Marshall that happened shortly after that, makes me think that I really was interested not so much in language or socially engaged art, but mainly in the question of how we can find freedom within the structures in life that confine us, including the gradual codification process that make us “academic”. The aging of of our bodies and our ideas is inevitable, but perhaps we can find freedom in acknowledging, and sometimes, even harnessing and even precipitating their arrival, stabbing that Dorian Gray picture à la Lucio Fontana. After all, it is always better for us to say the last word and leave in a high note than gradually withering until we are left only speaking to ourselves. And as I wrote in that 2010 text, “A public program lives a short and happy life, affirming the integrity and individuality of art and ideas, without the need to multiply or be given an artificial, extended, afterlife.”

We concluded the program with this poem by Emily Dickinson:

In this short life

that only lasts an hour

how much — how little –

is within our power