Over the last week as we started this new year, we were witnesses to a Brazilian version of the January 6th assault of the US Capitol almost to the day of its 2nd anniversary. The protesters “seemed almost to be cosplaying American insurrectionists,” wrote Yascha Mounk in The Atlantic. The Brazilian production of the Capitol attack felt even more like an off-off-Broadway farce because it happened on a weekend when the buildings in Brasilia were closed, Lula was already in power, and there was no official procedure to disrupt. Meanwhile, back in the actual US Capitol, the selection process of the Speaker of the House, hijacked by a far-right fringe group that pushed the sessions up to the 4th day and the 14th vote, creating a situation of such histrionic dimensions that the actress Julia Louis-Dreyfus wrote: "If we don't win an Emmy for this episode of @veephbo I'm leaving the TV Academy."

These types of events are also a reminder that we live in an era where different practices sometimes merge unexpectedly, and such has been the case of politicians who engage in performative politics, which more and more has been described by the press and the political class itself as “performance art” . New York Times Magazine’s Robert Draper said: “I think the loudest voices in the room are the ones who are far more interested in politics as performance art than they are in the nitty-gritty of governance." Representative John Yarmuth of Kentucky, a Democrat, said: “There are far more members here who are engaged in performance art and performance art only now, and they really have no interest in governing.” And last year, Teri Kanefield writing for NBC news described Marjorie Taylor Greene’s courtroom appearance about the role she played in the January 6th insurrection as “performance art”. The list goes on.

I doubt that many politicians or pundits have enough art knowledge, let alone a studio art or art history degree that would allow them to fully understand what they mean when they wield the term “performance art”. It is a bit dispiriting that the mainstream use of the term, even when utilized by those in the Democratic party, continues to have the disparaging and reactionary connotations inherited from 30 years ago, the time of Jesse Helms’ crusade against the NEA which led to, among other things, the withdrawal of support of the famous NEA 4 — performance artists Karen Finley, John Fleck, Holly Hughes and Tim Miller— as well as all future individual grants to artists. In other words, whenever “performance art” is now used in political punditry it is generally done to refer to vacuous, self-indulgent, immature and self-aggrandizing provocative actions. It has become a shorthand for self-promotional petulance, a direct legacy of the Helms era.

But as much as we might be loath to admit it, there is a performative strategy to current far-right wing antics that does resemble, to a degree, the strategies of artivism and the left. And for all the dislike I might have for the ideas of the Trumpian far-right conservatives, they have been effective enough in their performative antics to sow discord and chaos in the political system.

Trump himself is not such a unique figure in the history of performative politics. An important precedent is Silvio Berlusconi, a savvy mogul who knew how to weaponize the media and dominated Italian politics for three decades. One of his many performative stunts included launching a poster design competition making fun of his baldness in 2000 in order to neutralize the topic for the opposition (the slogan was “more hair for all”). And here we also need to set the record straight about the Mexican president Manuel López Obrador, whose populist style and frequent attacks on the press have often prompted comparisons of him being a left-wing version of Trump, when in fact he is a precursor.

In 2006, 14 years before Trump’s 2020 electoral defeat and Stop the Steal campaign, López Obrador lost the presidential election by a small margin to Felipe Calderón, and right away claimed fraud, thus starting a Stop the Steal campaign of his own. He then anointed himself as the “Legitimate President of Mexico” and staged a massive ceremony in Mexico City’s Zócalo where he symbolically took possession of the office — with some subtle modifications so that he would not be legally accused of treason or impersonating the presidency, such as using the 19th century version of the national emblem of Mexico (from the Benito Juárez era). The federal government seemingly did not know how to handle AMLO’s strategies but opted for tolerating him. In spite of the disapproval of 56% of voters for his actions, he used his symbolic title to remain a leading critic and a thorn on the side of the Calderón administration. Now the actual president, AMLO has continued his performative style, both in his daily morning press briefings (known as “las mañaneras”) and in a number of political stunts like the raffle of the Mexican presidential plane, (as AMLO argued it was a waste of money and announced that he would fly commercial). AMLO initially wanted to raffle the plane to the Mexican people; but the project was doomed from the start, as it became clear that the plane was rather unsellable and unusable for an ordinary Mexican citizen who would also need to spend a fortune for its upkeep. The raffle was then turned into a contorted lotto game with cash awards with various winners, and once the actual winners were announced some started enduring extorsion and threats from cartels who wanted to extract the money from them, as it happened to a small community in Ocosingo, Chiapas.

All this to say— and I have thought about this for many years— that it would be interesting to assemble a history of political stunts as if they were outsider conceptual art— not all of which, by the way, are cynical or demagogic. One of the most interesting and successful progressive politicians in this category —which has been an inspiration to many actual artists— is Antanas Mockus, who was mayor of Bogotá in the 1990s. His actions included filming a TV commercial of him in the shower in order to promote water conservancy, hiring 420 mimes to make fun of traffic violators (thus using public ridicule instead of fines in order to improve traffic culture in Bogotá) and promoting a “Night Without Men”, where men would stay at home to take care of the house while women and children would go out. After his mayoralty, Mockus has continued in politics, more recently in congress where he has continued performing— acts such as mooning congress as an act of protest against the treatment of its outgoing president, Efraín Zepeda.

Someone who appreciated the potential that performativity could have in the political discourse, and actively sought to teach potential global leaders about it, is the indefatigable Carol Becker, Dean of the School of the Arts at Columbia University and a leading thinker and writer who deeply reflects on the creative process. About 15 years ago, Becker went to the Davos Forum with Columbia’s president Lee Bolinger (attending Davos is something that university presidents often do) and came up with the idea to tailor a program for young future world leaders where they would become sensitized about the potential of creativity in live presentations. She described it to me thus:

I wasn’t sure how I could fit into such a business-oriented program but I met the then dean of the Global Leadership Fellows, Gilbert Probst and I asked him how they address the issue of presentation in working with young leaders and leaders-to-be. I assumed, and was correct, that they brought in people who do such speech/presentation training for corporations. I suggested they come to Columbia and we do real voice training as we would do for actors. So, they did come and Kristen Linklater (now deceased) and Andrea Haring who now runs the Linklater Center for Voice and Language and Brent Blair a master of Agosto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed and I designed a workshop that would take 5 days and would be intense training for the mind and body. It was a great success so we were invited to do a short version at Davos, which we did, and then the Global Leadership group continued to come to Columbia for the next 10 years just to get this training.

It was not performance art at all, but rather really intense immersion into voice and speech development done intensely and professionally by those who do the same for actors in training. It was a way for the Fellows to reenter their bodies. We added the Agosto Boal training to bring in social issues. Brent Blair is a true master teacher and he also was able to completely engage them in the Agosto Boal methodology. The Fellows loved this program and that is why it went on for so long. It was by far their favorite part of their training. Even those who were skeptical at first became converts since they could see their confidence as presenters and leaders strengthen as a result of reentering the body through voice and physical exercises designed to open up the voice. They also got to work with trained actors to perfect their public skills, presenting a short piece at the end that they each wrote for themselves and then worked on with our team to develop their presentation. But this was not a one time event, it was an ongoing relationship with the World Economic Forum that continued for a decade. It only ended as the Fellows program was cut back.

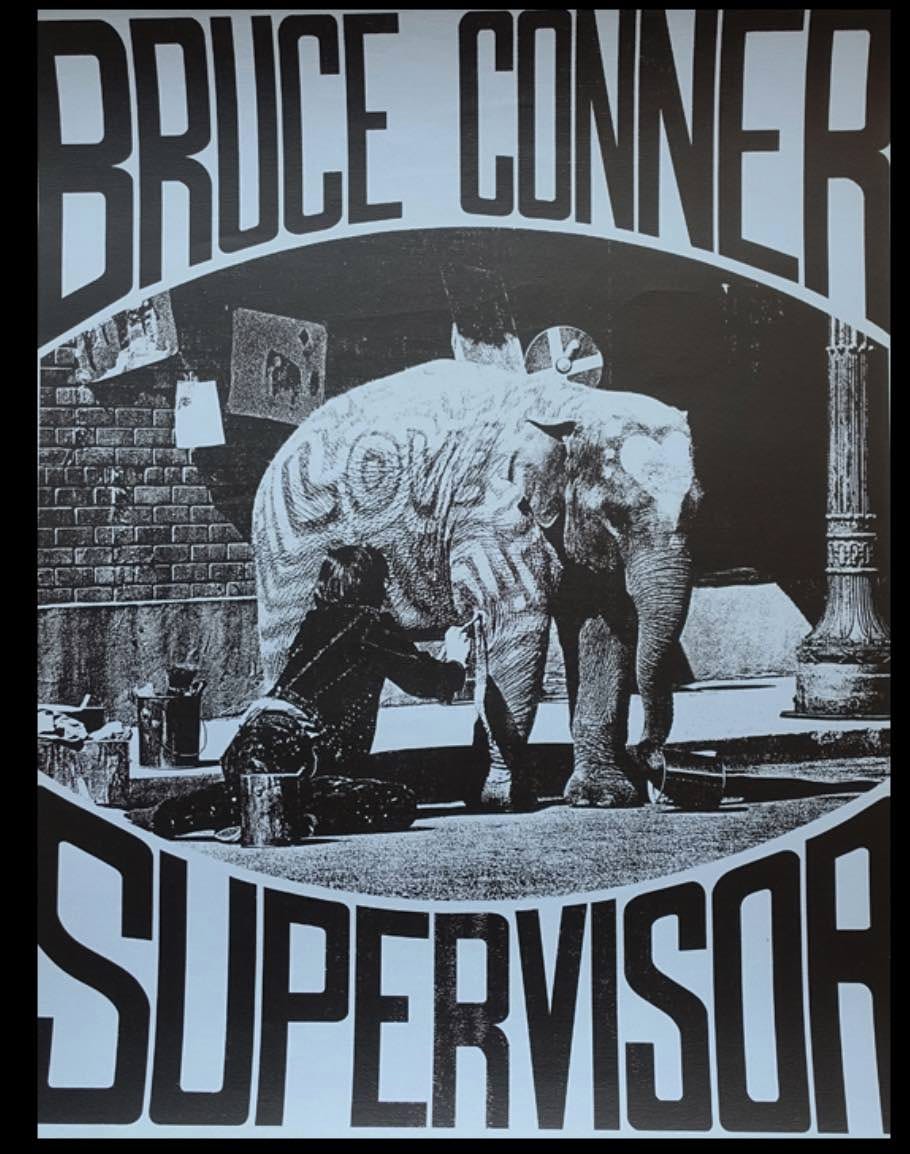

No less interesting is to examine how some visual artists have tried to appropriate politics into their practice. An example is Bruce Conner’s campaign for Supervisor in San Francisco in 1967. As Jean Conner (Bruce Conner’s partner) described it, “For him the campaign was more like a game. At that time there was no fee to run for supervisor in San Francisco. So it was free publicity. He got to give speeches to the public. He also got to publish at no cost in the booklet where the candidates listed their qualifications and positions. The speech he gave was a list of candies and desserts.” At the same time, Conner adds, “Bruce voted in every election and was very critical of friends who didn’t vote. Even if his was the only "no" vote, it was important to let someone know that someone had protested.’ Tania Bruguera, in 2016, declared herself as candidate for the presidency of Cuba, an act that was mostly a protest statement given that there are no legal mechanisms for an average Cuban citizen to pursue the highest office there.

There are at least two important takeaways from the compare-and-contrast exercise of the political actions that are creative (but not deliberate) artworks with the performative practice that is political (without explicitly trying to exist only in the political realm). The first is that it shows that creative demagoguery can have real and destructive effects in the lives of people because it is not the kind of activity confined to the fourth wall: people die due to stupid or evil politicians and the falsehoods they spread, not so much from a performance piece presented in an alternative art space. But the second takeaway is that it also proves that the expertise of the artist is not just about representation or the creation of fictions, but about using forms of communication that can also have a real and positive social effect.

As example, we are seeing the historic example of Volodimir Zelensky— a comedian who once played a president on TV and is now the real president of Ukraine, but who has intuitively and effectively used his talent to inspire and lead his people in an unprovoked war against Russia, further showing that art is also a means to show authenticity— and, while in the process, put in evidence the old-fashioned phoniness of political theater.

None better than Mockus to describe himself: “My idea of the artist is someone who, in a prison cell, takes a piece of chalk and draws a border to define his space, a person who has more restrictions than those normally apparent. But upon defining those restrictions himself, he liberates himself.” https://latoneriaypintura.co/2017/12/28/mockus-the-artist-mockus-the-idiot/

Love this piece. Thanks for bringing a clear mind to the insanity we are now confronted with daily.