The Portentously Queer Life of Death

Did an 18th century Mexican friar write the first gender-fluid novel?

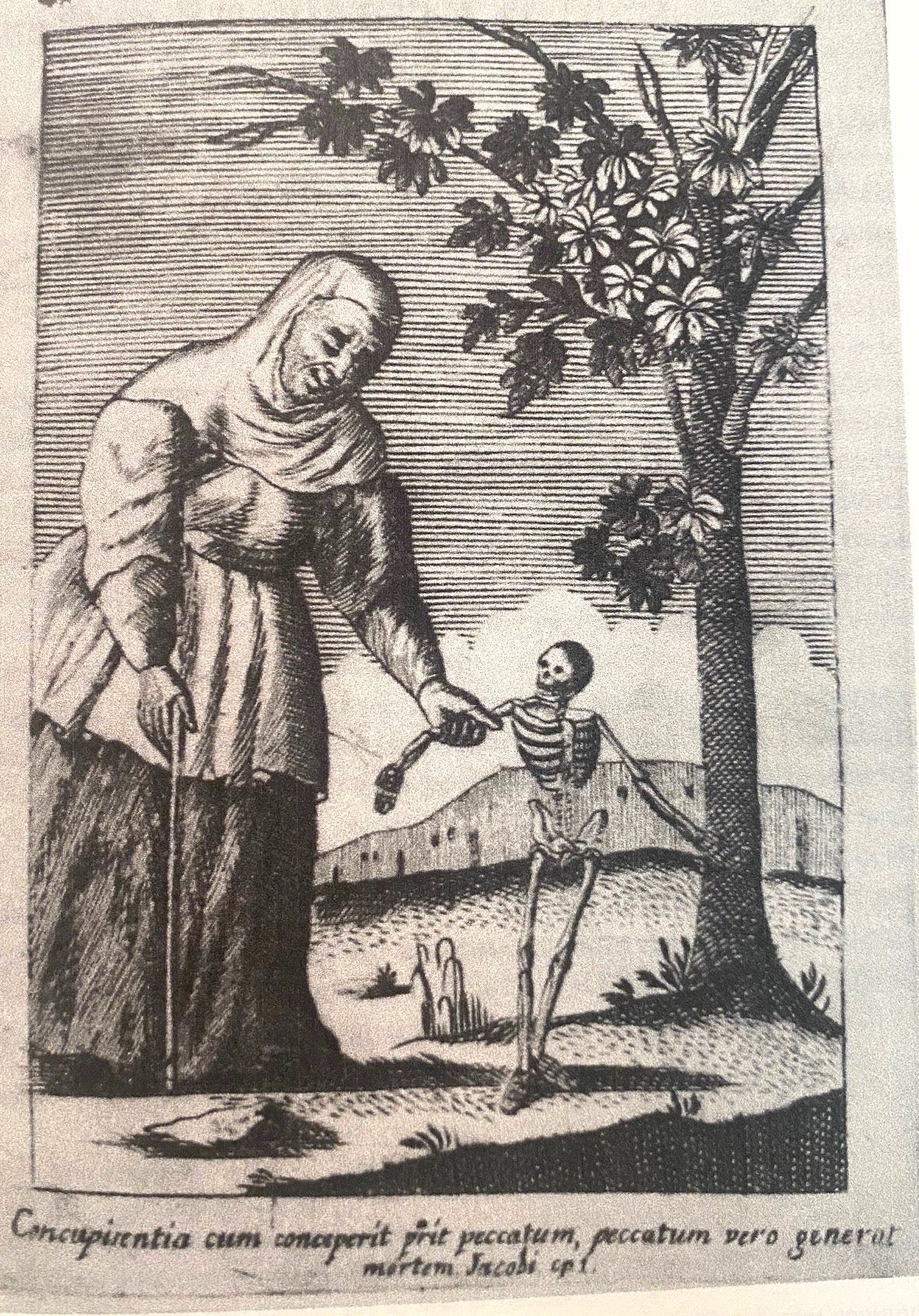

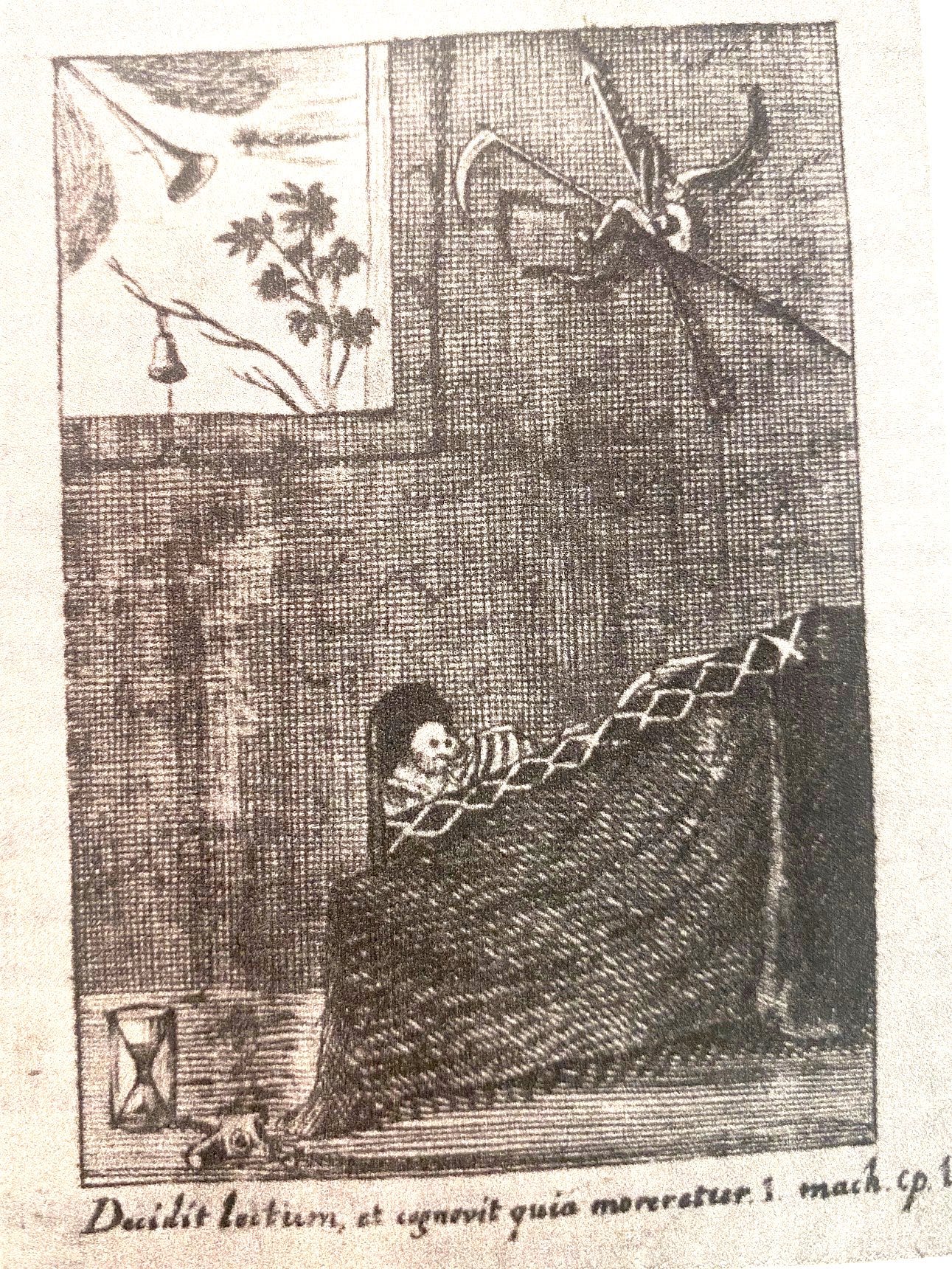

Death as a small child

The colonial period in the Americas, with its environment of superstition and religious hysteria such as the one that caused the Salem Witch trials, is an ideal literary setting for stories of ghosts and goblins (think of Sleepy Hollow, set shortly after US independence). Which is why in the proximity of the Halloween/Día de los Muertos holidays I have been thinking of an actual colonial-era novel, written in Mexico, one that centers on the dark theme of death but that takes it well beyond the macabre.

A few months ago I visited La Murciélaga, a used bookstore in Mexico City co-owned by my friend, the writer Luigi Amara. Luigi and I share a passion for used books and rare literary finds. It was precisely in conversation on that subject that he told me about the original edition that serendipitously landed in his hands of La portentosa vida de la muerte (The Astounding Life of Death), written in 1792 by Fray Joaquín Bolaños.

Bolaños (1711-1796) was a Franciscan friar who lived in the state of Zacatecas. His last name is not to be confused by the one of Roberto Bolaño, the Chilean novelist who gained posthumous international fame about a decade ago when his novel 2666 won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and who is also renowned for his novel Los Detectives Salvajes (The Savage Detectives). Fray Joaquín Bolaños, however, two centuries after his passing, has become a posthumous rock star in his own right in academic circles and in the geeky corners of colonial and death studies, and his novel has turned into some kind of cult classic. The book was printed with permission from the church but was soon after censored by the Inquisition. The first, 1792 edition is so coveted that La Murciélaga bookstore was able to sell it to the University of Toronto for a considerable sum.

Some scholars, like Maria Isabel Terán Elizondo, Professor at the Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, have argued that this work is a modern novel. And depending on the criteria used, it could also be argued that it might be one of the first, if not the first, Latin American modern novel (published 24 years before El Periquillo Sarniento, written in 1816 by José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi; many novels of pastoral and religious nature were published in the New Spain dating back to 1519). But there is at least another specific attribute that makes this work unique— and subversive.

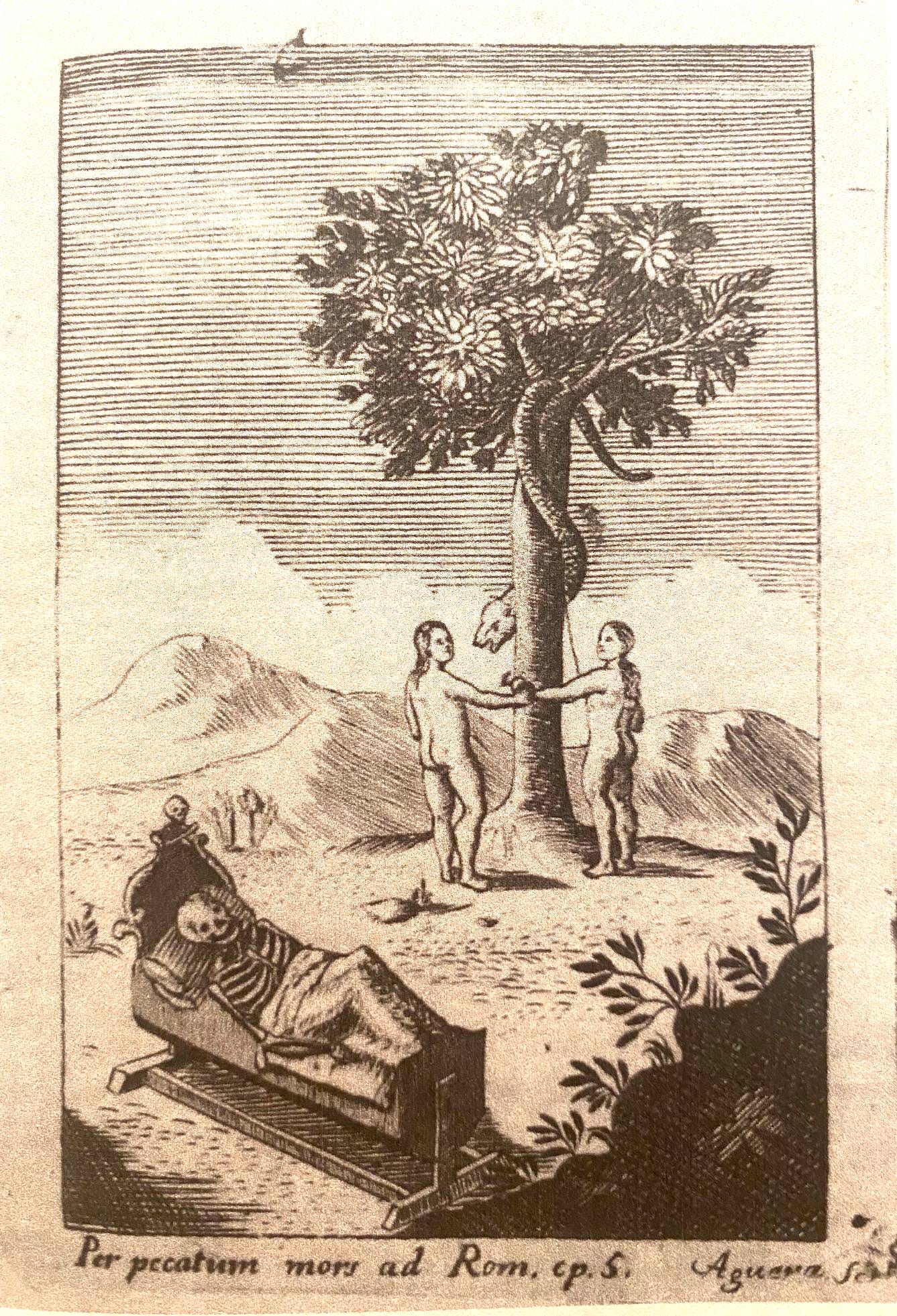

The birth of Death (as a result of the original sin)

The novel details the various and whimsical adventures of Death as the hero of the story, experiencing the life events of a regular mortal, inflicting the perishing of humans throughout. The fact that it is a fictional narrative that was allowed for publication— in colonial times fiction was associated with lying and blasphemy— makes the book even the more interesting. Fray Joaquín, in the introduction, goes through great lengths in explaining why he has taken this approach, wanting to provide a moralizing narrative about the virtues of a good life by using humor — a method, he argues, allows him to “dorar la píldora” (sweeten the pill) of moral didacticism for the reader (I can’t also help but to note that Fray Joaquín was 81 years old when the novel was published, a really advanced age for the period, which makes me wonder about how much the author wrote this work while coming to terms with his own, inevitably approaching demise).

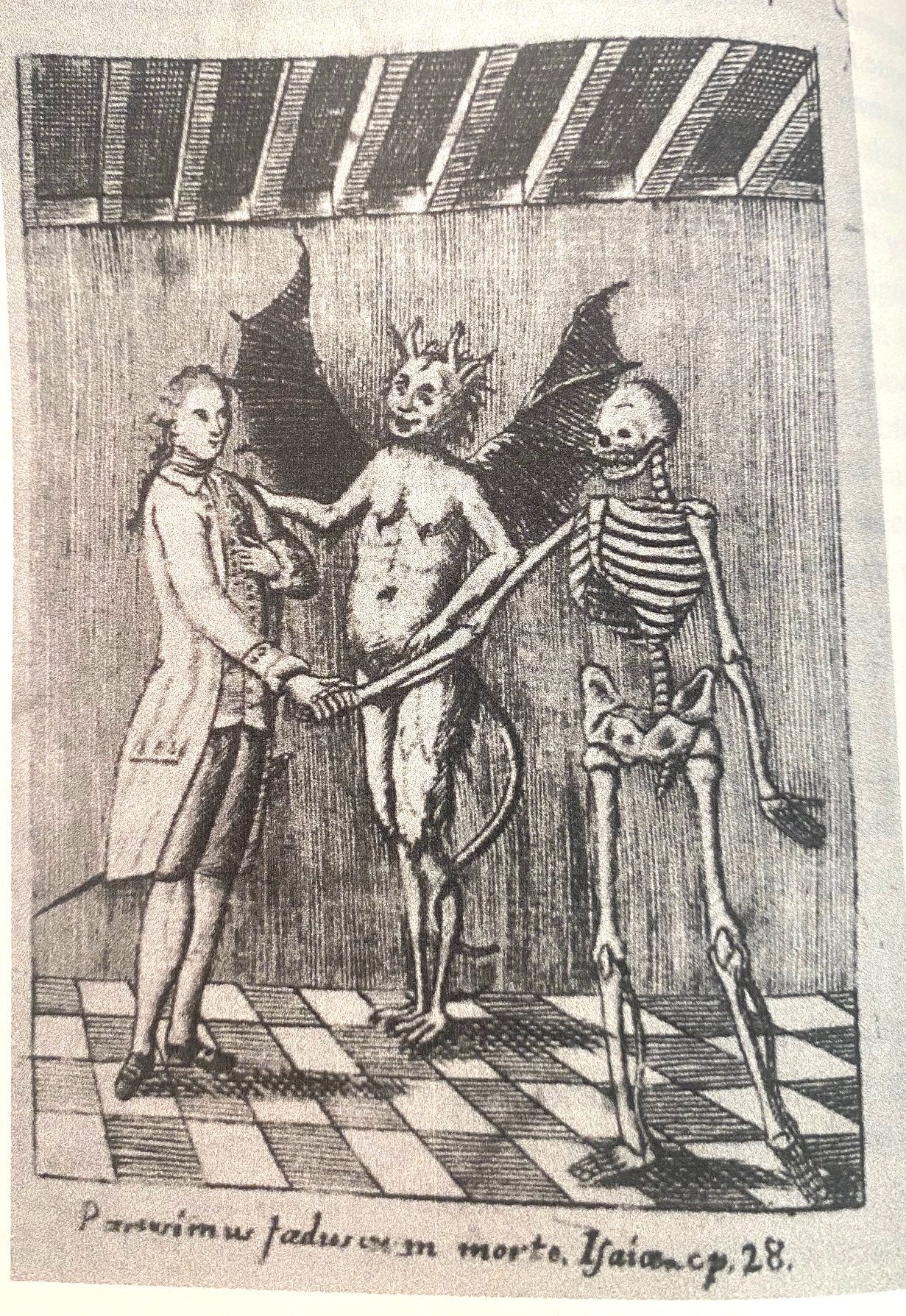

Death’s marriage officiated by the devil

Salvador Olguín, a Mexican writer based in New York who brought attention to the novel in recent years and is considered an expert on the topic, also shared his thoughts with me about the work. “Personally I think that Bolaños is a misunderstood innovator. While the work claims to have a moralistic and evangelizing purpose, […] there is a literary connection with the Cervantes of Novelas Ejemplares (Exemplary Novels). The influence of poems that came with the European genre of Danse Macabre (or death dance) is also notorious: it is a liminal text, hard to classify.”

The character of Death, which in Spanish is referenced using the female pronoun (“La Muerte”), is presented as female in the story, seeking various husbands (all of which expire as they go in bed with her, which is a frustrating experience for the protagonist). Nonetheless, the overall behavior of Death is fluid: she operates with a freedom and agency that would have never been permitted to a woman in colonial times, so in respects like these the character exhibits traits that are both female and male, existing in some ambiguous limbo. As Luigi was describing this peculiar aspect of the narration to me as we were standing in his bookstore, he remarked: “It’s like this is a queer novel!”

His comment stuck with me and I recently asked him to elaborate on his impression. He wrote:

“[in the novel] Death does get married with men, but since she needs to take care of both men and women and her goal is to get everyone through her scythe regardless, she also courts the opposite sex. Death of course is situated beyond any considerations of gender and her identity for the same reason is ambiguous and fluid. This reading is one of the approaches that make the book attractive to the contemporary reader, but I am not surprised that due to traits like this and because of its perplexing novelty it received a cold reception and was even condemned in the unwavering Catholic environment of the colonial society of the New Spain at the end of the 18th century.”

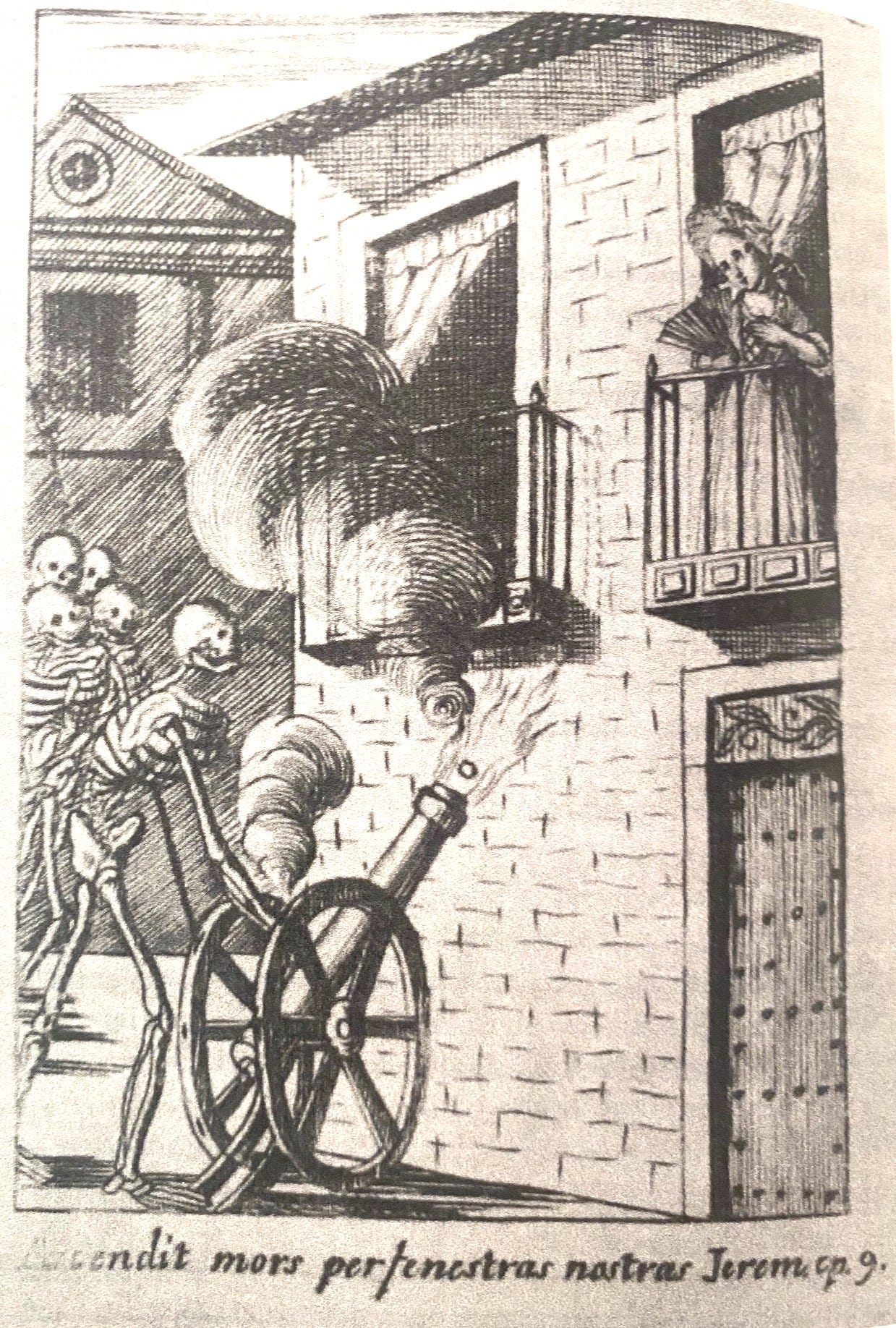

Death assaults a lady

Catholicism had a moral stranglehold on the society of the New Spain for centuries, one where acts of homosexuality would be punishable by death; but for that very reason it is even more interesting to see how the subject of the fluidity of gender at times appears in Catholic tradition. I inquired about this with Ray Hernandez Duran, who is Professor of Art History and Museum Studies at the University of New Mexico as well as a noted and respected Colonial art scholar. Ray replied:

Saint Liberata or Wilgefortis. Anonymous. Städtisches Museum Neunkirchen.

“There are saints who exhibit physical traits associated with the “opposite” sex, such as Saint Liberata or Librada, who grew a beard to avoid a marriage she didn’t want. By growing facial hair, she became masculinized and her female beauty was obscured thus making her unacceptable as a wife in the heteronormative context in which the narrative unfolds. An actual historical figure that stands out in line with this conversation on gender fluidity is Catalina de Erauso, the Basque Lieutenant-Nun, who was born female and lived her early life as a woman but escaped from a convent in Spain and sailed to the Americas in the 17th century. According to historical accounts, including her own autobiography, she cut her hair short, wore men’s clothes, and traveled to Peru where she lived as a man, got into fights, and wooed women. She eventually went back to Spain where her biological sex was revealed but was let go and she returned to the Americas, the second time, to New Spain.”

Catalina de Erauso, portrait attributed to Juan Van der Hamen, c. 1626

Explorations of ambiguity of gender in this novel abound. In an undergraduate thesis on the subject, in 2016, the young scholar Katlyn Rochelle Smith astutely argued, using the conceptual framework on liminality, that the character of Death in this novel both upends and evidences the ambiguities of the construction of gender in the New Spain.

I asked Hernandez himself to share thoughts on the gender-ization of death in art. He offered this:

“I would think that when Life is represented as female, it’s due to women’s ability to give birth and the maternal role they normally play in nurturing family life, all of which maintains humanity’s existence whereas men, who are typically the engineers of and/or actors in such things as warfare, executions, violent crimes, etc. may come to be associated with Death. Here, we must remember the ancient Greek/Roman god of death, Hades/Pluto, who governed the underworld and is personified as male, as is his offshoot, the Devil in Christian belief and also, Father Time, who, depicted as aged, associated with the end of the human life cycle, and sometimes holding a scythe, is synonymous with Death. Death is the final authority so it makes sense that it would be often gendered as male, given the patriarchal norms structuring the cultures in which such ideas and images circulated. On the other hand, Death comes to us all regardless of sex, class, race, etc. so that may explain why, at times, it may be depicted as sexually ambiguous and thus representative of humanity overall. Additionally, Death sometimes seems flippant, like a joker figure, given how random death can be.”

But if a queer interpretation of the novel solely on the narrative might not be convincing to some, another important element to consider are the illustrations that accompany it, attributed to the artist Francisco Agüera Bustamante. The engravings, which most definitely prefigure the popular Mexican depictions of death in the modern era, both help support the narrative interpretation of the character as a trickster and, as Olguin pointed out to me, emphasize its gender ambiguity, “which makes the illustrations all the richer.” He adds: “The engravings of Francisco Agüera Bustamante share the irreverence of the text and are some of the earliest examples of fully Mexican representations of death, in a tradition that was continued by artists like José Guadalupe Posada and that it reaches us through the paraphernalia associated with the Day of the Dead.”

The death of Death during the Last Judgment

My father, the eternal optimist, would always try to cheer us up whenever we encountered a setback or worried about a problem, always using the refrain: “todo tiene remedio excepto la muerte” (“everything has a solution except death”). Which may be true in more than one sense. Aside from the fact that death marks the end to every project and aspiration and that it is the great equalizer, the philosophical paradox is that death is in itself is never final as a concept – that is, it eludes definitive practical and intellectual definition. Those of us who have unfortunately experienced the loss of a loved one can attest to it: as much as one might have read and believe to understand it, the experience of loss is ultimately one of deep incomprehension. And because it eludes definition, when personified in art it can become the perfect performative vessel of liminality, becoming a disruptor on many of our traditional mortal beliefs— such as, for example, the duality of gender.