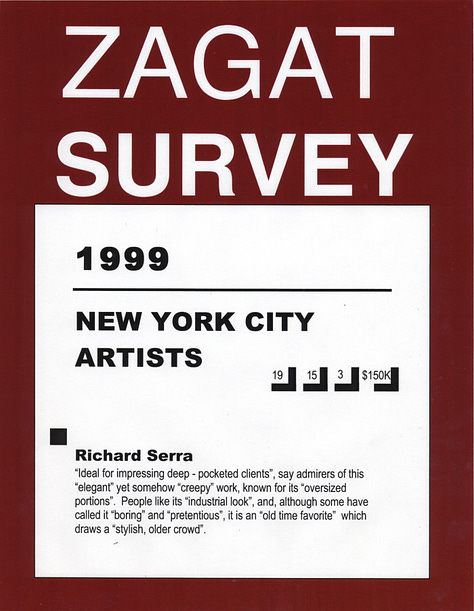

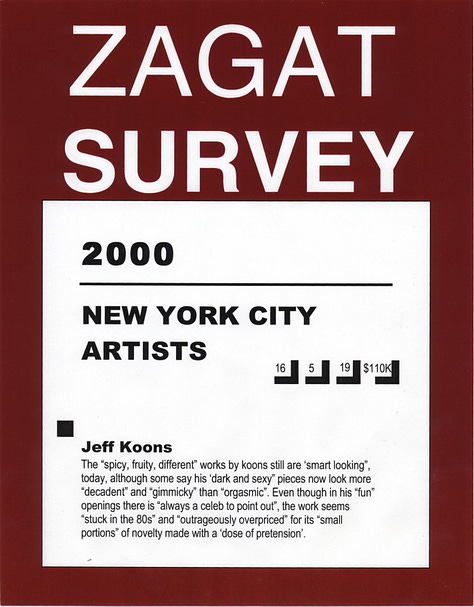

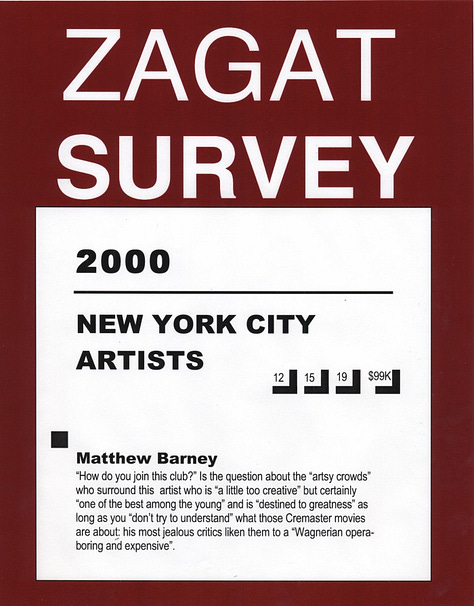

Among the many truisms about living in New York City, the one that usually tops the list can be encapsulated in the immortal slogan by the colorful activist, past New York gubernatorial candidate and readymade performance artist Jimmy McMillan: “The Rent is Too Damn High”. Of course this also applies to studio space. When I first moved to New York I could not afford one, so I had to arrange studio visits in my railroad apartment, which was difficult and embarrassing (once a curator reprimanded me: “this is not very professional, Pablo”). The first exhibition projects I did while living in New York I had to assemble at home from my Macintosh Performa computer (thinking back, it is symbolically interesting that they were mainly performative projects, and that this was years before I even got to meet and work as an artist with Roselee Goldberg). The very first one was a series of artist Zagat surveys, an appropriation of the format of the restaurant review publication that restaurants would display in a laminated form outside of their establishments (when they were positive). I used quotes from amateur food critics to describe the work of various artists, (using a steakhouse review for Richard Serra: “ideal for impressing deep-pocketed clients” and drawing from both Italian and Indian restaurant reviews for the work of Francesco Clemente: “this handsome and classic Italian”, “tastes like it comes out of Bombay”, but “you wouldn’t get these prices in Delhi”).

Unknowingly, I had become a post-studio artist.

My frustration for not having a space was somewhat alleviated when I learned that I was not alone. I heard stories about how great artists in NYC like Felix Gonzalez-Torres did not have a studio, keeping his preparatory drawings under his bed, and as I am told would mainly meet with curators in cafés to discuss projects.

There are quite a lot of examples of influential and celebrated artists, past and present, who did not/do not have a studio. They include Alice Neel (who worked in her apartment on the Upper West Side), Jack Smith, Michael Asher (whose Post-Studio course at Cal Arts became a gospel of sorts of this practice) Sue Coe (who reportedly once told the story that she would flip over her bed in her NYC apartment to work during the day and flip it back at night to go to sleep), Darren Bader, Mexican artists Mónica Mayer and Victor Lerma, and Gabriel Orozco especially in his early years when he used the city as studio in his work.

Joseph Cornell famously worked in the basement of his home on Utopia Parkway, and Tony Smith — as art historian and Smith scholar Joan Pachner confirmed to me— did not have a conventional studio but rather worked between two houses he had in South Orange (where he grew up) and neighboring Orange, NJ.

Hans Haacke works from his apartment. In reply to my inquiry he wrote: “For many years already, the works I thought of and made designs for at home, were, in fact, realized by people with the necessary skills and equipment. I am lucky to have found such people and am grateful to them.” Tania Bruguera until recently did not have a studio, “which is why I did so many residencies”, she told me. And Emily Jacir also shared with me that she made the piece that won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennial “working on a model on my bed” in a small Brooklyn apartment that sat atop a reggaeton bar.

Turns out that the kitchen is a favorite working space for many artists. René Magritte had a studio in his home in Brussels but preferred to work in the kitchen, as writer Katharina Cichosch tells it, “just as his habits in general contradicted much-repeated artistic clichés in certain regards.” Also, outsider artist Eugene Andolsek, a stenographer for the Rock Island Railroad, worked in his kitchen every evening making intricate abstract drawings that he stored away and never exhibited.

And an interesting case study to understand the studio/home relationship (with an emphasis in the kitchen) is the one of Louis Bourgeois, who after the death of her father in 1951 was plagued by a period of depression that also led to agoraphobia. In later years, even while she did frequently travel to Italy in the 60s and 70s and even got a studio in Brooklyn, she increasingly preferred to stay home— even getting her to go to Midtown Manhattan to visit MoMA (I was once told by curator Debbie Wye, who organized her retrospective there in 1982) was an effort. As her long-time assistant Jerry Gorovoy once said, “the more famous Louise became, and the more public recognition she received, the less she wanted to go out into the world.” Bourgeois’s home studio on 20th Street in Manhattan was famous, primarily for being open to visitors every single Sunday in the form of a salon. Today its layout helps understand some aspects of Bourgeois’s working process. As I recall hearing, her kitchen table where she worked largely determined the size of her prints, and her printing press was located in another room in the house, so Gorovoy would go back and forth from the kitchen to the press making proofs to bring to Bourgeois (and, per his own telling, sometimes take them away as she had a propensity for wanting to destroy her own work).

Daniel Buren is one of the most famous artists who also are studio skeptics. In his 1979 October Magazine essay The Function of the Studio, Buren speaks of how the studio space limits what can be produced there by virtue of pre-establishing coordinates that only are later reproduced in the museum or gallery: “by producing for a stereotype, one ends up of course fabricating a stereotype”, which is preceded by this foundational statement: “the definitive space for the work must be the work itself.”

In my conversations with various fellow artists on their own feelings about studios I found other commonalities. Even while acknowledging the fusion of art and life as an aspect of the artist’s profession, most also recognize the benefit of being able to separate work from the living space. Even when you are not an object-maker you are well-served by having a space separate from home where you can think. A 2006 study in the Journal of Vocational Behavior found that the separation of work and home life is positive in that it helps us give greater focus to each component of our lives and thus achieve greater balance.

Another point revolves around the recognition that an artist studio, like other material goods, is ultimately a status symbol: the larger it is, and the more assistants you have in it, the more it advertises the artist’s success, so not having a studio can be a source of shame even for artists who are widely recognized for their work. Even though we know the size of a studio is a frivolous way to measure an artist’s stature, it still tends to function as an indicator. And one can say there is such a thing as “studio envy”, especially when one sees that in other cities studios are more affordable, such as in Mexico City, where many artists have studio spaces in interesting and culturally vibrant neighborhoods.

Then again, there is no denying that we live in the post-studio era, and while certain artists must have a physical space due to the nature of their work, the ability to work entirely online and conceptually is much greater than in the past. New media artist Lev Manovich told me: “I have worked only on laptops in public spaces like LA hotel pools and cafes since 1999. But now that I allowed myself to make more art, may one day get a real ‘studio’”. Manovich also added that he dislikes coworking spaces: “I think of coworking spaces as factories of Information Age, and I like to be different. I also love people watching and normal life and outdoors and movement and variety. So good cafes are perfect for me.”

And I was also reminded of multimedia artist Allard van Hoorn, who was the very first artist that I knew whose practice was entirely nomadic. When I first met him, around 2008, he only carried a laptop and a compact external hard drive that held his entire oeuvre, right before the use of cloud storage became widespread.

I often think of the artists who moved to SoHo in the 1960s and 70s, some of which still live in lofts that they use less as studio space and more as storage and offices. Given the fact that my generation missed the affordable SoHo loft-era, it led me to think about — and I being ignorant on the subject might be misguided— the relationship between the increase of conceptual, post-minimalist practices and the prohibitive costs of real estate in the Big Apple. So I asked art historian Alan W. Moore, who is one of the most knowledgeable experts on the history of artists and real estate in New York City, to share a few thoughts on this subject. His response: “The SoHo generation, and the Seaport Coenties Slip bunch had space in abundance. I understood really their production as primarily sculpture in close dialogue with performance & dance” [in reference to artists like Richard Serra, Lee Lozano and Trish Brown]. “My sense was that the conceptual work, ‘immaterial’ work was directed towards the gallery environment – the white cube – and didn’t have so much to do with the living space of the artists. Big space by conceptual artists was used for hosting meetings. The biggest change came with the loss of (relatively) cheap big space – (all programmed by the real estate ‘industry’ of course), and the shift to apartments which Loisaiders used as studios. So a return to salon scale work like School of Paris, i.e., classic bohemia.”

There are also many contemporary examples of how the inevitable real estate limitations faced by artists in places like New York have produced great apartment projects. In 2008 Mexican artist Blanka Amezkua created The Bronx Blue Bedroom Project, a space literally in her bedroom in Mott Haven in the South Bronx, which she also used as her studio. “My intention”, she once wrote, “was to create an intimate art space where contemporary artists exhibited their work in a setting that differed radically from the already established art venues.” Later the project evolved to become AAA3A, (Alexander Avenue Apartment 3A), still functioning today. Each featured artist is invited to “offer a workshop related to their work or to prepare a delicious meal for friends and neighbors.”

Last but not least, there is the question of what a post-studio performance art practice looks like. I had to confront it as a teenage performer. There was a bathroom on the top floor of our family home, adjacent to the laundry room, seldom used. I loved how echoey it was; there I sang renditions of E Lucevan le Stelle, Vesti la Giubba and other opera hits. One day my sister told me: “You know, every evening I hear a man next door singing opera. Its hilarious! I want you to hear him, but every time he starts singing I can’t ever find you.” My decision to finally confront my mortifying amateurism head-on led to The Metropolitan Opera Bathroom, an opera performance at an apartment show in NYC organized in 2008 by Krista N. Saunders, where I serenaded visitors through a plastic curtain while they sat on first toilet row. Studio or no studio, resourcefulness always trumps budgetary constraints, and the show must go on —because artists are too damn dogged.

With thanks to Joan Pachner, David Maroto, Rosanna Marrtinez, Marc Fischer, Coco Fusco, Aaron Landsman, Marco López Valenzuela, Shelly Silver, Trong Nguyen, Robin Winters, Brian Boucher for their input.