In the early 90s I was in Chicago, recently graduated from art school and starting my museum work life. I had been away from Mexico for several years and had scant opportunity to return, so I often felt homesick. I had kept in touch with a few of my closest friends from high school. Because it was the pre-internet era, we would correspond via regular mail, often with elaborate and long handwritten letters describing the intricacies of our everyday life. One of my best friends was, and still is, Luis Padua (who is now a noted journalist and editor in Mexico, and who has given me permission to tell the following story). Luis would send me regular updates about his studies (he studied communications at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana in Mexico City) and his early involvement in left-wing activism. At some point he sent me a 20 page-long letter telling me the account of his visit to San José del Pacífico, a small town that sits at 8000 feet above sea level on the Sierra Madre Occidental, somewhere between Oaxaca City and the Pacific coast. He told me about the magical aspect of this town and the hallucinogenic mushrooms that grow there. His description of his experience was so powerful that it made me want to go there. We agreed that we would go together on my next trip to Mexico, which happened sometime in 1994. Luis managed to get yet another of our friends, Eduardo, to join.

We took a bus from Mexico City to Oaxaca City, and from there we had to board a “pollero” bus toward Pochutla (a long-distance second-class bus called that way because they tend to be packed and passengers often bring live animals on board). we boarded the crowded bus with lots of people pushing against us. Almost right away I realized that my wallet was gone. I was upset, but both Luis and Eduardo encouraged me not to worry, offering to lend me money. We would not let this incident ruin our trip.

The bus ride up the mountain was long and bumpy. Gradually, as the bus went up the mountain, we started to feel the cooler temperatures. It is often remarked that San José del Pacífico is located “en las nubes”, because of the fog that results from the moisture in the air and the temperature that drops below the dew point. For about two hours the bus went through endless turns up the mountain in the middle of the fog, with almost zero visibility. Then, at some point, we emerged from the fog, and we encountered a mysterious forest with luscious deep green vegetation where its trees and sharp contours drawn by the cool midday light. I felt that we were arriving in some kind of enchanted forest.

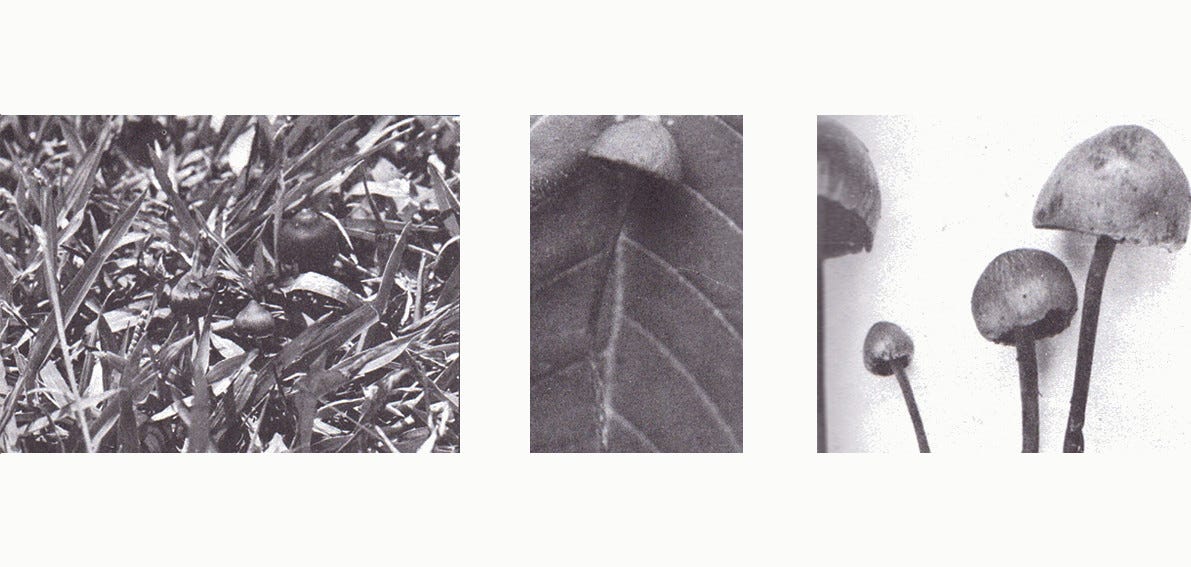

We then arrived in the town, a small collection of humble huts and home of only a few hundred inhabitants of Zapotec descent. There is no clear information of when the town was founded, except that it did not become known by external visitors until the 1960s, when hippie tourists began to arrive to experience its hallucinogenic mushrooms (Psilocybe Mexicana). Due to its climate, these mushrooms grow in all sorts of areas, over leaf litter and decaying wood.

Luis led us to an area where there were very simple accommodations— some wooden cabins that would rent for only a few pesos. Whenever an outside visitor arrives in San José del Pacífico locals assume that they are in search of mushrooms, so they offered us some them right away. After getting settled and procuring mushrooms, Luis told us that he had a “ritual”, adding: “I like to eat them in the mountain”. He suggested that we should go onto a trail that led to a river, as the experience would be more powerful if we were in the middle of the forest.

We walked down the path for about 45 minutes. At some point we saw a disheveled, tall blonde man— he looked German— walking by. “Some of them end up living here”, told us Luis. He talked about one called “La sombra” (“the shadow”) who lived below the town.

After a while, we stopped to rest and consume the mushrooms, which take about 30 minutes to have an effect. We had been instructed by Luis not to have breakfast so that the effects would be strongest. At first, I did not feel anything, which is common. I myself was skeptical about the power of the mushroom, or at least of the idea that it would have any impact on me. As we were sitting in the path, Luis started to talk about the effect the mushrooms were already having on him and discuss the spiritual experience that they bring. I remember becoming increasingly adamant about arguing that there was no such thing as the spiritual, which led to a sort of theological discussion where I vehemently argued against the existence of God. I did not realize how obsessed I was becoming in my argumentation, nor that my arguments, in a certain way, were starting to feel like visual representations in my mind.

Gradually, I started sensing that everything around us was alive: the trees and plants, appeared to be palpitating and breathing like animals. “You sense the tree’s absorption of water, the tree bark as breathing skin,” Luis recalls. The experience was so intense that I forgot about my philosophical disquisition and for a very long time we all were in deep silence. I remember feeling, and then saying out loud, that I would be perfectly happy with staying there forever, living under a rock on the side of that road for the rest of my life. The plenitude I felt was so powerful that I didn’t need anything else from the world, society, fame and fortune be damned.

At some point, we heard a noise. A rancher was coming from below the path toward the town with a couple oxen. I remember being highly impacted by the image, and I read the ox, which had a light orange color that strongly contrasted with the green of the forest, as being on fire. After the rancher passed with his cattle, Eduardo then said: “was that real, or was that the effect of the mushrooms?”

At some point we continued walking. We completely lost track of time, but we must have been in the trail for about six hours, because by the time we got back into town it was dusk. We had long conversations and a certain hilarity dominated us— seemingly anything made us laugh. The effect of the mushrooms was easing at that point. By this time the fog had lifted completely, and one could appreciate the majestic mountain landscape of San José del Pacífico.

When we arrived in the town we were absolutely starving (we, of course, had not eaten all day). We went inside a small shack that doubled as some kind of dining establishment with only three or four tables where according to Luis we had enfrijoladas, but all I remember was basically a bean soup with some hard tortillas. Even though it was such a basic meal, I remember it as it being the most delicious dinner I had ever had in my entire life. The mushrooms had produced in us a remarkable appreciation of the sensorial world: every taste, every image, every smell, and every texture felt incredibly complex and rich.

--

In the 1960s, very few US-based writers of Latinx descent had broken into the mainstream, and their works were not widely disseminated. The exception became Carlos Castaneda, a Peruvian-born, naturalized US citizen who in 1968 published The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge. The book, a classic exploration of the world of shamanism and of altered states of consciousness through the eyes of an apprentice under the guidance of a Yaqui Indian sorcerer, has sold 10 million copies in the US and been translated in 17 languages.

Castaneda is an outlier in practically every respect. He did not come from literature: in the book, Castaneda, who studied anthropology at UCLA, claimed that his book was an ethnographic account of his apprenticeship with Don Juan Matus, an indigenous Yaqui sorcerer originally from Sonora who lived in the Southwest. Don Juan introduces Castaneda to the “teachings” drawn from the psychoactive alkaloids like mescaline (“mescalito”) found in the peyote plant, which gives those who use it access to what is often described as “non-ordinary reality”.

Castaneda’s book was presented (and accepted) as part of his doctoral dissertation at UCLA, but over the years it was very criticized by anthropologists and often dismissed as a work of fiction. Probably because of both the success and the subsequent scholarly scrutiny that he received, Castaneda himself became a highly reclusive figure (reportedly using at one time a surrogate to pose for his portrait). He disappeared from public view shortly after a Time magazine cover story in 1973, where he was praised but also confronted with the discrepancies in his life, saying”; "To ask me to verify my life by giving you my statistics ... is like using science to validate sorcery. It robs the world of its magic and makes milestones out of us all." The success of this book likely stemmed from its accessible narrative, which appealed to non-specialists. While it may not qualify as a true ethnographic study of shamanism, it played a significant role in raising awareness and sparking interest in psychedelic drugs, indigenous cultures, and mysticism, particularly during the countercultural and pop movements of the 1960s and 70s. It’s not unreasonable to think that some of the first hippies who flocked to San José del Pacífico in those years were influenced by Castaneda’s work.

And, like many others in high school and college in Mexico, both Luis and I also read “Las enseñanzas de Don Juan” at some point. I asked Luis whether this book colored his way of thinking about the experiences with mushrooms (even though the book centers on peyote). First, Luis pointed out that in the psychedelic/psychotropic community, the common wisdom is that “o eres peyote o eres hongo” (“either you are peyote or you are mushroom”), meaning that your personality is naturally aligned with one of those drugs. “In that dichotomy, I am mushroom”, Luis said.

Then there is the topic of the mystical insights that the experience provides. Luis also spoke about how up to that period he had been atheist (which was rather in-keeping with his involvement with the political left in college), but that after those experiences he had discovered “certain spirituality”: “I felt that all creation goes much beyond, that there is a divine space.”

After my last conversation with Luis, I found myself reflecting on what that experience had meant for me. I feel I am not a passionate disbeliever as I once was, but my views on a personal god remain unchanged: while I acknowledge that one can’t ever been absolutely certain of anything, I live my life under the assumption that there is no divine hand behind it all. I believe we arrive in this beautiful world for a brief moment, and when we vanish, the only traces of us left behind will be the work we've done and the memories others hold of us.

Yet, my time in San José del Pacífico did teach me something important. As an urbanite who has always lived in sprawling cities and felt uneasy with the silence of the countryside, I came to appreciate my connection to nature. I am alive along with the trees and plants around me, part of the same intricate web. And while I may never choose to live beneath a rock in a forest, surrounded by lichen and trees, I always carry within me their essence and the mysterious fog that envelops them.