The Unbearable Cuteness of Being

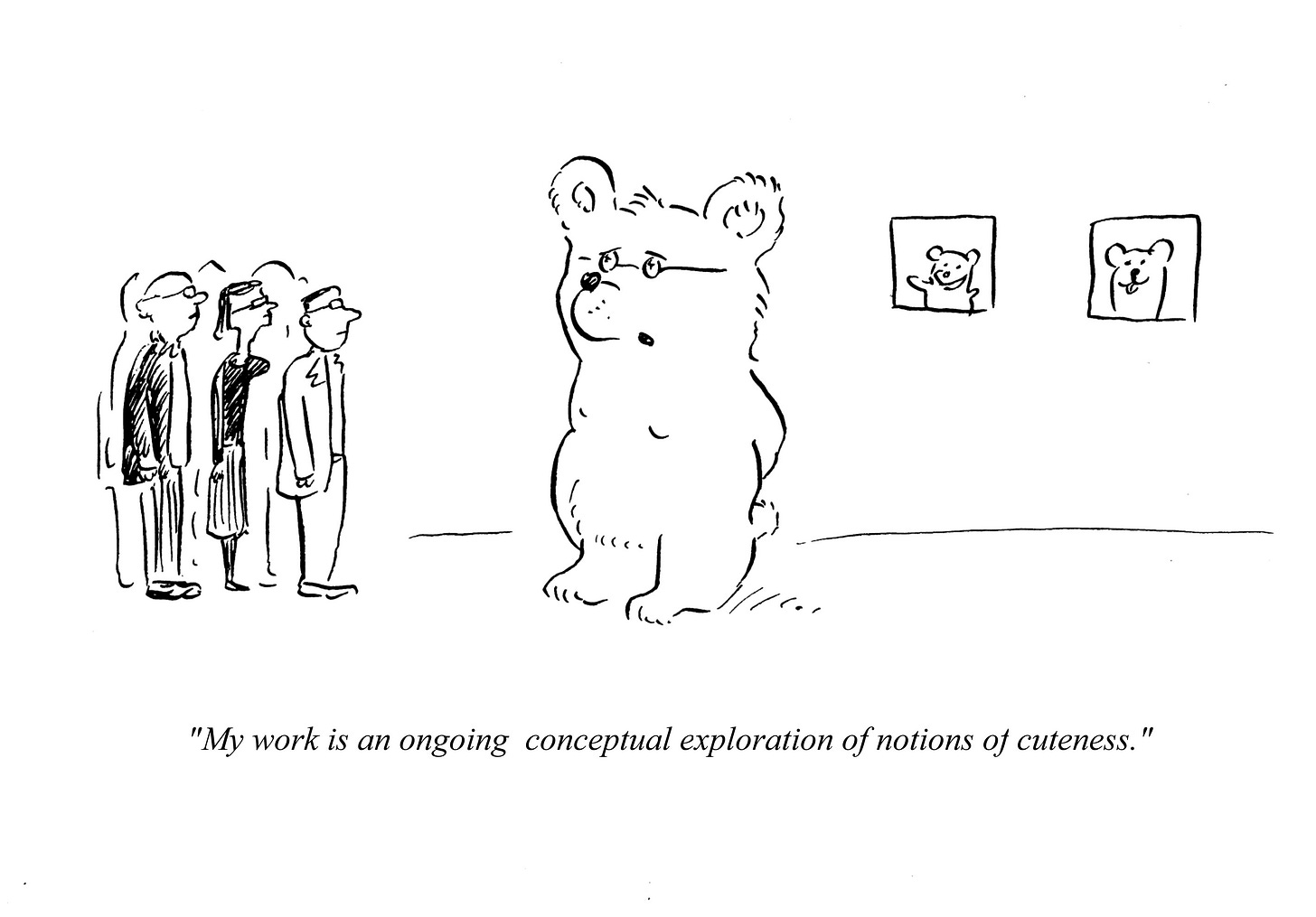

The problems posed by being adorably unaware— in art and otherwise.

Once, in conversation with a very famous artist, he told me that he didn’t care about what people said about his work, “but one of the things I really can’t stand is when they say I am a poet.” He thought that speaking of his work as “poetic” was really denigrating.

Ever since this artist made that comment I have thought about the truly hurtful or humiliating things that I people have said to me about my work. Interestingly, and similarly to the artist I mentioned, the criticisms are not the ones one would normally hear from a critic concerning manufacture, level or artistry, intellectual import, or contemporary relevance (all of which, I suspect, are always in the mind of a professional artist anyway and it can even be a fixation). I was instead told by a curator that a participatory education program I had designed was “cute”. So there, I have said it: cuteness is my pet peeve.

This curator’s condescending comment (not unusual among elite curators commenting on education programs) was clearly meant to make light of whatever I was doing, even if on the surface it was presented as a compliment. The subtext was that the activity was infantile, superficial, lacking sophistication, and ultimately unworthy of serious intellectual consideration. “Cute” becomes a way to relegate certain people and things to the province of innocence, or, if you will, to the kid’s table.

I felt the need to set aside my feelings about the issue in order to understand a more interesting, and perhaps complex problem: can cuteness ever be taken seriously, in an artwork or otherwise?

The way we culturally understand cuteness (in the case of people, who they are and what they do) is in fact rooted in the principles that govern evolution and are inextricable from two interlinked components, the first being visual and the second behavioral. In 1943, Austrian zoologist and ethologist Konrad Lorenz introduced the concept of “Baby Schema” (“Kindchenschema”) to refer to specific physical traits in newborn and young offspring (big eyes round and large head) that instinctively motivates caretaking amongst adults and helps ensure the survival of the species. Which is, in a way, an extraordinary masterpiece of nature: if we did not think babies were cute —if instead we found them repulsive— our species would likely perish in short order. In 1980, Stephen Jay Gould famously wrote about the topic in an essay titled “A Biological Homage of Mickey Mouse”. In that essay, Gould traces Mickey’s inverse “evolution” over 50 years as a cartoon character, from his “birth” in “Steamboat Willie” to the present (or at least up to the time when Gould was writing). As he showed, while the normal human evolution is that our head and eyes become more proportional in relation to the rest of our bodies, this Mickey however, “has traveled this ontogenetic pathway in reverse during fifty years among us. He has assumed an ever more childlike appearance as the ratty character of Steamboat Willie became the cute and inoffensive host to a magic kingdom.”

Gould took the task of scientifically measuring Mickey’s evolution very seriously:

“To give these observations the cachet of quantitative science, I applied my best pair of dial calipers to three stages of the official phylogeny--the thin-nosed, ears forward figure of the early 1930s (stage 1), the latter-day jack of Mickey and the Beanstalk (1947, stage 2), and the modern mouse (stage 3). I measured three signs of Mickey's creeping juvenility: increasing eye size maximum height) as a percentage of head length (base of the nose to the top of rear ear); increasing head length as a percentage of body length; and increasing cranial vault size measured by rearward displacement of the front ear (base of the nose to top of front ear as a percentage of base of the nose to top of rear ear). All three percentages increased steadily--eye size from 27 to 42 percent of head length; head length from 42.7 to 48. 1 percent of body length; and nose to front ear from 71.7 to a whopping 95.6 percent of nose to rear ear. For comparison, I measured Mickey's young "nephew" Morty Mouse. In each case, Mickey has clearly been evolving toward youthful stages of his stock, although he still has a way to go for head length.”

What might have motivated this gradual transformation? I have no idea what conversations Walt Disney might have had with his cartoonists, although I imagine it was less a conscious correction toward cuteness than an instinctual, progressive series of renditions that sought to satisfy the way audiences responded to the character, rendering him more and more youthful and cute than before.

The second aspect of our instinctive recognition of cuteness is the fact that it is a condition where the cute person in question is not aware of their own cuteness. This attribute (lack of awareness) that is natural in all babies, puppies, kittens and so forth, gives the subject a level of vulnerability that inspires tenderness and love.

So why would this matter in art anyway? Believe it or not— and I am going to really go out on a limb here— I suspect that it lies at the very core of the psychological relationship between curator and artist.

A key role of the curator is the one of reader and context-builder; artists are expected to make. The curator’s role is to find the artist and to cast them in the adequate context, and for that to happen artists need to allow themselves to be read and contextualized (which is why it is traditionally easier for curators to curate dead artists). I can’t help but to see a relationship between the nourishing instinct of the adult who takes care of the cute baby and the curator who discovers a young artist and sees something in the work that they feel is important and can be best appreciated when placed in a particular contemporary or historical context. It of course has nothing to do with being physically adorable, or even young, but it has a lot to do with the condition of not being self-aware of a particular aspect of one’s own work that is later pointed out (and contextualized) by others. And in fairness, the curator-artist relationship in these cases is not the one of a nourishing parent but instead closer to the anthropologist to their subject.

Another trait of cuteness that also applies to the art practice is that it can hardly be artificially created. Certainly I know many successful artists who have cultivated a persona of naiveté and humility, one that can give others the impression that they can be in control, but they fool few.

An exception, are, of course, the eccentrics—those who truly live in their own world and largely are unconcerned about the way in which they are seen by others. A case in point might be Yayoi Kusama, whose ubiquitous presence all over the world (including the automaton painting the windows of the Luis Vuitton store) recently prompted artist Mira Schor make a comment on social media (which got some push back) about how that display is in a way a metaphor of how the artist has become a malleable curiosity and even a managed brand without her own awareness:

“The reason the automaton of Yayoi Kusama painting polka dots in the window of The Louis Vuitton store at the corner of 57th and Fifth Avenue is creepy is not just for the reason automaton are intrinsically fascinatingly creepy because they almost perfectly replicate a living being but also because the actual living being Yayoi Kusama has as far as I can tell long been a front for a production industry in which she plays very little part.”

It is a trait that often puzzles us and make us wonder of the degree of introspection and control that artists like these might have (or not) on their own work and careers. But at any rate, it is interesting to also see that some artists who are naturally drawn toward those eccentricities consciously make the decision that they should simply trust their instincts without rationalizing them too much. I remember once another well-known artist once saying at a lecture I organized of him something to the effect of “I sometimes feel it is important to make work without thinking too much about why I am doing it.” It is something that for one reason or another has become a kind of mantra for me. It is not that I secretly wish to be a cute baby again (and I am thankful I will not be) nor that I wish to descend to a state of uncritical unawareness, but we all can be well served by taking moments of play, of experimentation and pursuit of our deepest obsessions that can for a moment take us away from overwrought conceptualizing and strategizing— even if those who are too stiff and stiff upper lip might dismiss those efforts as naïve.

As an aside, is interesting for me to think about the fact that this curator who once made fun of me, now retired, accomplished little of intellectual import in his career; he was a gray high-level administrator whose largely academic exhibitions have now been forgotten. And yet his disproportionate self-regard (like the ever-growing baby head of Mickey Mouse over the decades) was so out of touch with reality that, come think of it now, it was sort of cute.

"I can’t help but to see a relationship between the nourishing instinct of the adult who takes care of the cute baby and the curator who discovers a young artist and sees something in the work that they feel is important and can be best appreciated when placed in a particular contemporary or historical context."... this is so true and so similar in the film industry between producers/agents and film directors.

Yes. Koons’ balloon dog is sooooo cute.