The Valley of the Uncanny Wonderland

Wax figures, toys coming alive, and the holiday joy to be found in the strange.

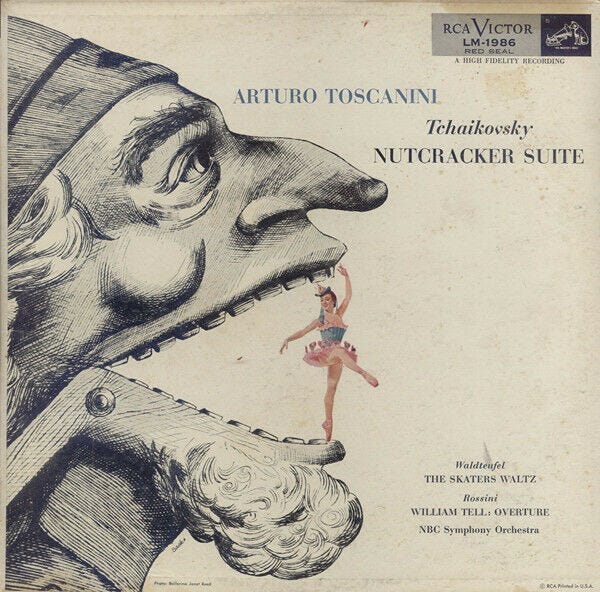

This past weekend I attended three performances in a row of The Nutcracker—not because I am such a fan of the holiday classic, but because my daughter, who is starting her life in ballet, was in it— and we wanted her to have a familiar face in the audience at every performance. As I sat in the dark theater witnessing the movements of the sugar plum fairy, the flowing snowflakes and the waltz of the flowers, I started reflecting on my own childhood fascination with the character of Drosselmeyer, Clara’s mysterious uncle and godfather— an old toy maker and magician with an eye patch who gifts the nutcracker doll to Clara. In the first book of The Nutcracker that I knew, illustrated by the extraordinary Adrienne Segur, both Drosselmeyer, with his mischievous grin, and the wooden-jawed figurine caused in me a degree of fear and fascination. In his enigmatic persona as well as in the magic toys he creates, Drosselmeyer embodies the archetypical traits of an artist.

The subject of a non-living entity that comes to life was common in the romantic era (think of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein), one that the author of The Nutcracker and The Mouse King, E. T. A. Hoffmann, favored. In his short story Der Sandmann, the narrator/protagonist Nathaniel falls in love with Olimpia, the supposed daughter of his professor Spallanzani, a woman who later turns out to be an automaton. The story is incorporated in Jacques Offenbach’s opera The Tales of Hoffmann and was also adapted for another ballet about a dancing doll, Delibes’ Coppélia. I grew up watching the flawless rendition —with total muscle and vocal control— of soprano Luciana Serra as Olimpia in the 1981 production of The Tales of Hoffmann at the Covent Garden, one of the greatest moments in opera.

While I could not have articulated it then, these were my first encounters with the uncanny, mediated by storytelling. It is a subject that has been fertile ground of exploration in modern art and in contemporary art practice, starting with surrealism —think of Hans Bellmer, for instance— and reaching a high point in the 90s, a decade in particular where there was a late post-modern fascination with erasing the boundary between reality and fiction, with artists such as Cindy Sherman (check out Sherman’s deliciously strange IG feed), Stan Douglas and Hiroshi Sugimoto. Incidentally and pertinent to this reflection, Douglas’ 1995 Der Sandmann, draws from Hoffman’s story, Freud’s citation of it in The Uncanny, and postwar Germany as it confronts its own history.

But photography, as a medium that is commonly associated with the representation of truth, is perhaps the most fertile ground to explore the uncanny. Sugimoto produced around that time a series of photographs of wax figures in Madame Tussaud’s Museum. Commissioned by the Deutsche Guggenheim in 1999, the portraits initially included Henry the VIIIth and his wives: Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour, Anne of Cleves, Catherine Howard, and Catherine Parr. Sugimoto made other works for the series of statues that are in that museum, ranging from political figures like Fidel Castro and Yasser Arafat to— continuing with the British royal theme— Princess Diana. The Diana photograph, taken only two years after her tragic death, is particularly eerie because it feels extraordinarily lifelike, and should one not know that this is indeed a wax figure it would easily appear to be yet one more portrait of the most photographed woman in the world during her lifetime— a testament both of the (shall we say, uncanny) resemblance achieved by the wax sculptor and Sugimoto’s masterful staging of the photograph.

Sugimoto comes to mind particularly because the concept “Uncanny Valley” was first articulated in Japan in 1970 by robotics professor Masahiro Mori when referring to the lifelike verisimilitude of human representations (such as robots, augmented reality or photorealistic animations) and the emotions they elicit in a person—a topic that has obviously come to the forefront in 2023 with the latest advances, and looming threats, of AI. The “Uncanny Valley” term was built from Ernst Jentsch’s psychoanalytic concept of the uncanny created in 1906, and later used by Freud in his famous 1919 essay, where he offers what would be perfect definition of many of the art works I described above: “an uncanny effect often arises when the boundary between fantasy and reality is blurred, when we are faced with the reality of something that we have until now considered imaginary, when a symbol takes on the full function and significance of what it symbolizes”, including the famous phrase, “The uncanny is that species of the frightening that goes back to what was once well known and had long been familiar.”

The reason why have always been interested in the unexpected appearances of the uncanny during the holidays (even if they might seem more appropriate for Halloween than for Christmas but they are not) is twofold, and I almost feel I don’t need to even explain it to anyone professionally involved in contemporary art: first, because (to state the obvious) in our sugar-coated, Disneyfied world of today there is no allowance for any ambiguity in the varieties of human joy: instead, in this “most wonderful time of the year” we often feel an imposition of commercial happiness that many often resent and even try to avoid (I think of my friends who really do not like Christmas season, and not for religious reasons) and which causes the aforementioned holiday stress. Secondly, as it is well established in the history of fairy tales, over generations these have always been much more authentic representations of the human experience, depicting death and injustice as well as love and harmony (in the case of the Sandman, this figure was said to steal the eyes of children who would not go to bed and feed them to his own children who lived in the moon). But the uncanny in the case of fairy tales (holiday ones and otherwise) is more than just frightening (with apologies to Dr. Freud): it is a form of wonderment. What replaces this authenticity and uncanny wonder in the modern era is cloying and incessant renderings Mariah Carey of “All I want for Christmas is You” and Jose Feliciano’s “Feliz Navidad.”

I hope I have not appeared Grinchy in my reflection: I do believe that we all should be allowed a degree of corniness this time of year (as I implied in my column last year during this time) because the holiday season serves in a way as a form of escapism— a parenthesis we create to focus on our closer social and family circles. My point is that in this period where we reenact the holiday rituals of the past it is important not to just go through the commercial motions but to also appreciate those interstices— so often expressed through traditional and modern art forms— where the tensions between the fictional and the real can be found. To me, in fact, the search for the uncanny is what has always brought me joy, in both childhood and adulthood, in art and in life, and I know that most of us who eat and breathe art, our extensive Drosselmeyer admiration society of sorts, feel the same.

So, to summarize: keep Christmas weird.