(Note: recently, NPR launched My Unsung Hero from Hidden Brain, a special podcast series that shares the stories of individuals whose generous actions had a positive and lasting impact in the lives of others. In that spirit, I am contributing the following story.)

Those who have navigated the complex career path of an artist usually keep a long list of individuals who played a key role in their formative years and without whom they could have never become who they are today. I often talk about how I personally owe infinitely to my parents, my siblings and my aunts, from which I learned the love of art but also the basics of work ethic and moral responsibility.

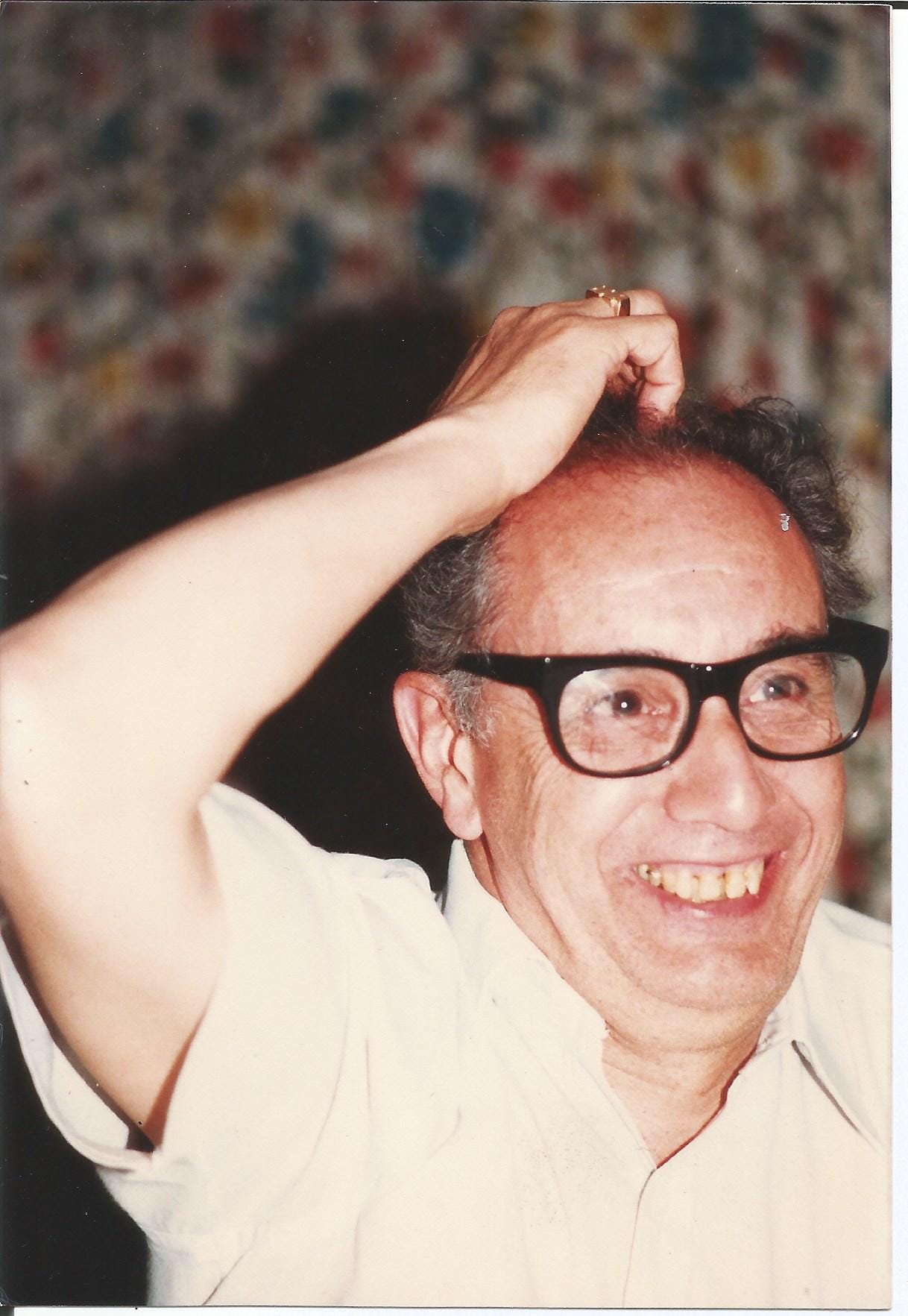

But going beyond immediate main family nucleus, I have also thought about who could be one of my unsung heroes, or, as I would also term it, a quiet mentor— a person who turned out to be very important in my artistic upbringing that almost no one knows about. I have been thinking about one in particular who sadly is no longer with us and who I regret not thanking publicly during his lifetime; one who gave me invaluable early inspiration and moral support: my uncle Juan Manuel Alarcón.

My father, who had to close a large bathroom and tile supply company in the 1970s due to financial struggles, subsequently reopened a new, micro-version of the same business from home, branded “Helguera y Compañía”, by retrofitting our home’s garage in Colonia Nápoles in Mexico City and turning it into a small showroom of which I have written about in the past. Of all the employees he once had the only one that faithfully remained with him throughout the closure, transition and reopening was literally family: my mom’s cousin, Juan Manuel.

Juan Manuel’s daily job, as executive business manager, was to produce invoices, estimates, conduct business over the phone, and handle correspondence, while my dad spent all day on the road visiting clients, closing sales and making deliveries. Because the office was at the entrance of our house, I would see him every day as I returned from school. “Hola Abo”, he would say (using the nickname that stuck to me since I was 2, when I could not properly pronounce my own name). Juan Manuel would sit all day at his desk, busily typing invoices making copies with carbon paper on his beloved 1960s Remington typewriter, which was the only professional typewriter we had ( and one that my brother, then in college, liked to take to his room during weekends to type his papers, which my uncle did not love; on Monday mornings he would be forced to come into the house and, tentatively standing by the stairs that led to the hallway next to our bedroom with my brother still fast asleep, start calling his name asking to get his typewriter back).

In 1985 I was 14 years old and fascinated by literature and opera. During the occasional Sunday family reunions I would be bedazzled by my mom’s brothers, my late uncles Enrique and Eduardo Lizalde, who were famous figures in Mexico’s cultural scene (Enrique was a soap opera star and Eduardo a famous poet). The whole Lizalde family were serious opera fans. My uncles and aunts often competed with each other investing in ever-fancier sound systems with the latest inventions of digital reproduction technology from the US (this is the era when CDs first became commercially available, as well as the then very fancy Laserdisc technology which was the precursor to DVDs) and also tried to outdo one another with acquiring the latest versions of opera production recordings featuring stars of the period like Domingo, Pavarotti, Norman, Freni, Caballé, and others. The weekend gatherings were interminable lunches that would merge into dinners and after-dinner conversations populated by cigar smoke, tequila, wine, and cognac. The gigantic speakers would blast opera at such decibel levels that the house often felt like it was shaking as in a mild version of one of those fearsome Mexico City quakes. I was only a kid, an insignificant and inconsequential audience member, hearing them with their deep and authoritative voices in conversation about politics, culture and of course opera (looking back, I wish Pierre Bourdieu would have been present at those gatherings as they would have really informed his thinking and could have helped him write an interesting epilogue to his 1979 work Distinction).

I wanted to learn about opera but I didn’t know how to go about it. So I turned to my uncle Juan Manuel in the home office. He shared the same family passion, although he never pursued a professional artistic career. He nonetheless had a group of hard-core opera aficionados who religiously got together one Friday every month to listen to historic recordings.

When I approached Juan Manuel (not without certain hesitation) to ask him about this subject, he was delighted. He would talk to me on and on about opera— evidently a great respite for him from the grueling office work he had to do every day, to the point that I remember worrying that I was distracting him too much from the work he needed to do for my dad. He then started bringing me recordings in cassette tapes he made at home (all of which I still keep) of those operas. The first was Il Campanello by Gaetano Donizzetti, followed by other operas including some of his favorites, Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier and Arabella (which has a famous duet that he loved and which always reminds me of him). Because he was born in the early 1920s and started collecting opera since he was a teenager, he had a priceless collection of 78 and 45 RPM records. I would listen to those recordings and discuss each version with him. Fascinated, I would hear about the famous singers he heard in his youth at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in the 1940s and 50s, regaling me with anecdotes such as the time when Maria Callas, performing Aida at Bellas Artes in June of 1951, surprisingly sang a near-superhuman E Flat toward the close of the Triumphal Scene that completely brought down the house and became one of the most legendary moments in the history of recorded opera.

In 1989, my family moved to Chicago. My father closed his business shortly before that time, and as a result I lost touch with my uncle, even though we spoke over the phone every now and then.

While I never became an opera singer, that teenage exposure to opera and particularly to the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk that opera embodies, likely informed my later interest in performance art and in multi-disciplinarity, narrative, scoring and the use of drama.

In later years, Juan Manuel saw me as if I were a famous artist, which I found ridiculous and made me blush with embarrassment. But even while he had an oversized image of me, I always appreciated his tireless cheerleading and enthusiasm. In our brief conversations over the years when I visited Mexico or we spoke over the phone our interactions sometimes reminded me of Alfredo, the projectionist from the film Cinema Paradiso, who guides a young teenager Salvatore in the art of film and encourages him to go out into the world to become a professional artist.

In 2012, I had a solo exhibition at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, the very place of which Juan Manuel told me so many stories about going to hear legendary operas. He strenuously insisted on attending the opening, I was told, in spite of the family’s concern for his frail health. And attend he did, a 89 year-old man in a wheelchair, negotiating the architectural maze and multiple marble stairs that conform the grand vestibule of Bellas Artes.

The following year, when I was launching Librería Donceles, a social practice project in the form non-profit used Spanish language bookstore, and I was asking for used book donations in Mexico City, he called me. He had assembled several boxes of invaluable old books from his personal library that he wanted to donate for the project. They were the books of his youth: Spanish-language translations of novels by Emilio Salgari, Edmondo de Amicis, Rudyard Kipling and other authors who constituted the go-to international literature for young readers in the Spanish-speaking world of the 1940s. I remember telling him “Tío, I can’t accept you giving me these books—they are too valuable, they are collector items”, and his touching response to me: “I want you to have them for this project: I will not be around much longer and I want to make sure these books go in good hands.”

Juan Manuel passed away at 93, in 2016. There were no national news or cultural reportage about his passing. But his impact was deep and lasting for many, and certainly in my case. He never once asked anything of me; yet what I received from him was priceless: most importantly — and something that I only understood many years later, as an adult, an educator and an artist— was the very simple lesson that the love for art is both independent of, and more important than, the pursuit of social or professional status.

I attribute my admiration of the pure, disinterested investment in art exemplified by Juan Manuel to my instinctive skepticism of the cult of connoisseurship. While I am the first one to advocate for the need for and importance of the engaged and critical study of the arts, we all know that a pitfall of connoisseurship is the tendency toward the formation of discriminating hierarchies where knowledge becomes a gatekeeping mechanism and a frivolous status symbol. In other words, Bourdieu: “Taste is first and foremost distaste, disgust and visceral intolerance of the taste of others.”

In Cinema Paradiso, after Alfredo dies and Salvatore, now a film director, returns to his hometown for Alfredo’s funeral, he realizes how the professional world he now lives in (and perhaps his very own persona) is riddled with affectation and pretense, the opposite of the authentic world which Alfredo embodied.

All proportion kept, as someone who had left their country to become an artist I recognized that divide all the same. I think often about the authenticity inherent in that kind of lifelong dedication where the desire to fully experience art is the true goal, and not the compulsion to narrate or flaunt one’s knowledge of it to assert one’s status. It is a quality that at times can make the projectionist, at least in that respect, sometimes stand above the film director.