Yesterday, as I was preparing a lecture about national symbols and how they are constructed, I had a personal family recollection— not one that I could have shared during that lecture, but that I will share here.

The year is 1986, in Mexico City. I am 15 years old, and I am painting incessantly, wanting to become a muralist. It is clear to my family that I need an art instructor. My parents, whose world is really the one of classical music and literature but not so much the visual arts, try to figure out options.

Then one day my dad has an idea: “we should bring him to my cousin Pancho”.

Francisco Eppens Helguera was part of the second generation of muralists, a group of artists who directly followed on the steps of Orozco, Rivera, and Siqueiros, starting sometime in the 1940s. He was Swiss-Mexican (Eppens’ father was born in Switzerland, and his mother, the cousin of my grandfather, was from San Luis Potosí, where Pancho was born).

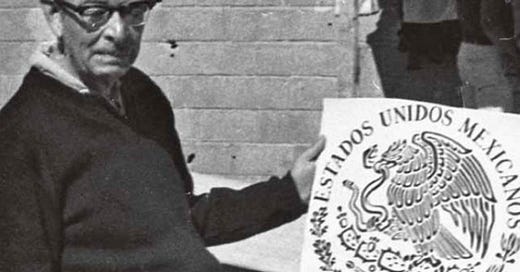

He is primarily known for his mural at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Mexico —one of those artworks that is recognizable to millions, even while the name of the author is not. Another work of his, one that has been seen by every single Mexican (and one who most don’t know who made it) is the 1968 version of the Mexican coat of arms, still used to this day in currency and in all official documents. The story of Pancho Eppens is thus the one of an artist who made highly public artworks, so many of them deeply engrained in the collective memory, yet who remains largely unknown, partially —I believe— due to his own unassuming and quiet nature.

Eppens’ 1968 Mexican coat of arms design

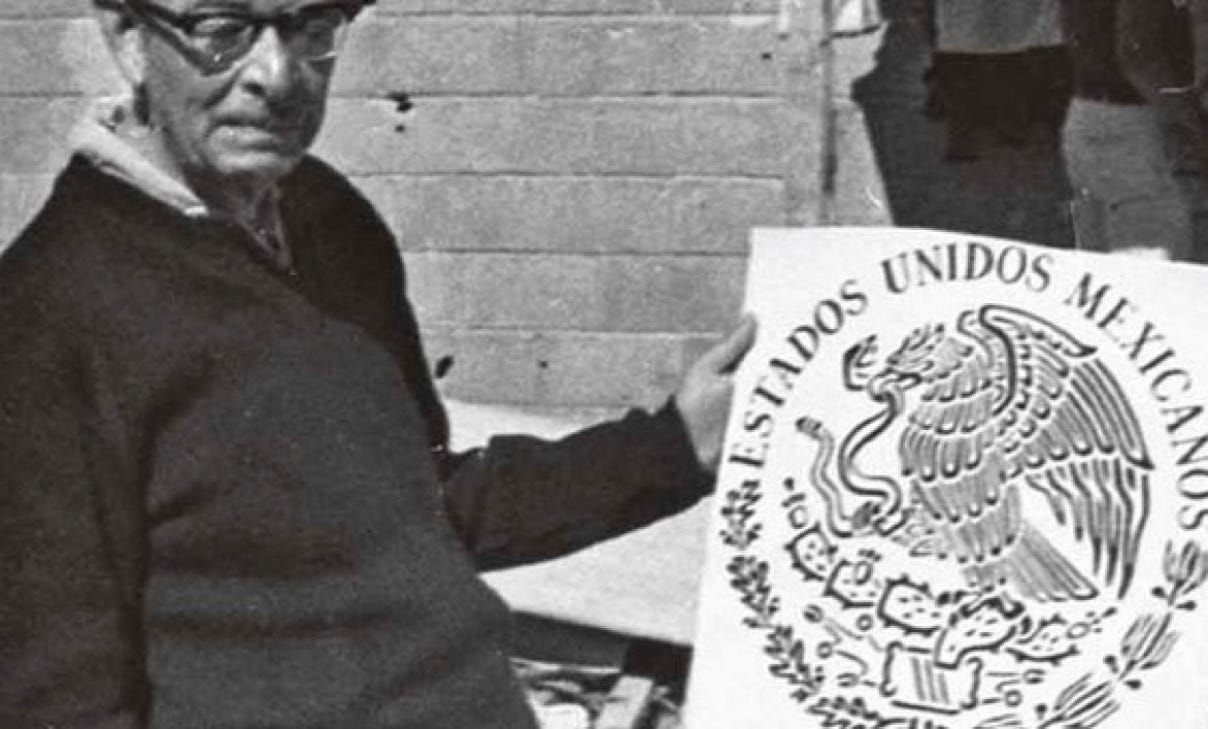

Eppens, mosaic mural in the faculty of Medicine building, UNAM, 1952

My dad took me to meet Pancho. He received us in his house in Colonia Del Valle. He had an ample studio with wonderful natural light, and his house was filled with his large social realist canvasses.

Pancho was a short, delightful, and self-effacing man in his seventies, bald with a thin mustache and black-frame, thick glasses in front of his bright blue eyes. My dad would often remark how odd it was that a man with such a flaccid handshake would be capable of painting enormous, powerful, and muscular figures onto public buildings.

During our visit, my dad explained to Pancho that I needed an art instructor and asked him to take on that role. Pancho was very polite, but in his typical, smiling shy fashion quickly told my dad that he had never taught in his life, and that he did not have the slightest idea of how to teach.

“You should take him to Enrique Zapata”, referring to an artist friend of his who taught art classes to small groups in a modest painting studio in Colonia Condesa. We did go to Zapata a few weeks later, but my parents were not thrilled when my first class featured a nude model.

So my dad brought me back to Pancho, this time begging him to teach me and offering to pay. Pancho refused the money but agreed (even if somewhat reluctantly) to have me come to the studio on Saturday mornings.

That first Saturday I arrived we both were nervous. I brought a white canvas, my oil paints, and brushes.

Pancho said: “vamos a pintar unos magueyes” (“let’s paint some agave plants”).

I had never painted a maguey in my life, so my initial charcoal drawing on the canvas was not very convincing. Pancho took me across the street to look at some agave plants that were growing on the sidewalk. I then endeavored to make a (rather poor) desert plant landscape with my new first-hand knowledge.

The next canvas I worked on included some human figures. I remember him taking out some yellowed and disintegrating anatomy books from his youth he had in some cabinet – they looked from the 1920s— to show me how to draw biceps. True to what he had warned, he didn’t know how to teach, but if he had any pedagogical style, it was essentially a mimetic approach— that is, teaching me to draw exactly like him. That notwithstanding, I absolutely loved it and would enthusiastically come every Saturday to paint dramatic muscular, indigenous figures amidst epic struggle in true muralist fashion.

Most days he would simply sit on a large leather armchair behind me in the large studio, chain-smoking in silence, staring at the void, while I painted (the mixed smell of turpentine, oil paint and cigarette smoke defined that era for me). It was odd to have my back to him, laboring without knowing if he was at all paying any attention to what I was doing. His occasional cavernous cough from smoking often startled me.

Every now and then, like non-sequiturs and totally unprompted, he would suddenly break his silence and start telling me anecdotes about El Rancho del Artista, a small property in the sparsely populated area of the city in Avenida Coyoacán (not far from his house) that had been redeveloped in the 1920s by the artist Francisco Cornejo to create a small artist community. Diego and Frida, as well as Dr. Atl and other important artists of the period often visited and were part of the artistic and social activities there. It was through these interactions and experiences that Pancho’s art career started in earnest, along with his joining the Escuela Mexicana de Realismo Crítico (Mexican School of Critical Realism) in the 1940s. He had known Diego and Dr. Atl well. I once asked him about what he thought of Rivera. “What always impressed me the most about Diego— he replied, after a long silence— was his capacity to work. He could paint for hours on end, with unbelievable stamina.”

One day, after a year and a half or so of Saturday classes, he told me, somewhat jokingly: “I am going to give you a vacation”. I understood perfectly. That day became in effect the end of my art lessons with him. Shortly after, I left Mexico to attend art school in Chicago. Pancho passed away in 1990.

Eppens was a superb draftsman with a natural intuition for composition. He had started his career designing postage stamps for the Mexican government, and his graphic talent — with the slight Art Deco aesthetic that characterizes a lot of Mexican muralist work of the 1930s— was no doubt the reason why he was asked to redesign the Mexican national coat of arms, and why the design still is used today.

But just like his teaching, his aesthetic was entirely about reproduction: he was in essence a highly skilled maker of images that fell within the very established lexicon of Mexican revolutionary iconography. Like other artists of his generation, he went on to take many public building commissions of the 40s and 50s that basically repeated the models and visual rhetoric of the first muralist generation.

Looking back, I realize I became the exact artistic opposite of what Pancho was— he being someone only and exclusively interested in formal variations of basically the same content, while I, shaped later by conceptualism, could never imagine sacrificing the primacy of content over form.

And yet, political and aesthetic philosophy aside, there is something liberating about how that relationship never was a problem for Eppens. Like a Baroque composer, the rules were firmly pre-established, all that was left was to elaborate the form, and the demands of the practice lied in making that form successfully with the purest craftsmanship. I sometimes wish I ever felt unconflicted about that approach toward art making.

Every now and then I remember that my unsuccessful 1986 desert painting is still around, hiding somewhere in my mom’s storage in Chicago. I must decide whether to destroy that painting or to keep it as an embarrassing souvenir of an unrealized muralist career, and of the story of a teenager who could not figure out how to properly paint the most elementary component in Mexican art: a cactus.