Those of us who were in New York City on September 11, 2001 will be haunted by that date for the rest of our lives. It is a day that most of us would rather forget. But the question that never goes away, and presents itself to us every 9/11, is how and if we want it to be remembered. This persistently unresolved question is embodied by the 9/11 Museum in Lower Manhattan.

Almost immediately after the terrorist attacks there was a collective effort to create a memorial for the World Trade Center. Initially called the World Trade Center Memorial Foundation, the National September 11 Memorial & Museum was formed as a 501 c 3 non-profit corporation to raise funds and manage the memorial's planning and construction. The memorial opened on the 10th anniversary of the attacks; the museum opened to the public in 2014.

I had never felt the desire to visit. The day after 9/11, all of downtown south of Canal Street was closed to non-residents; the smoldering remains of the towers continued there for months. It is likely that the psychological barrier to the site remained in me even after the memorial, and finally, the museum, opened to the public.

A few days back I conducted an informal social media poll with my fellow New York friends on whether they had been to the museum and the memorial. The vast majority said no, citing various reasons. One of my friends lost her husband who was a passenger in one of the planes, which is information that she did not even feel comfortable in sharing. Artist Nina Katchadourian wrote: “It feels like a memorial for outsiders, and I have plenty of my own memories as someone who lived through it.” Another friend wrote that he worked there as a tour guide albeit “under protest”, adding, “those of us who were here (I was downtown when the first plane flew in), it’s too emotional and painful to relive that horrible day.” And curator Sarah Bancroft wrote: “ I had wanted to write a “back page” for The New Yorker or NYTimes Mag after 9/11 saying essentially, “no, I want to forget.” (In response to the national outcry, “We will never forget!”) I’m not surprised to see others respond here that they have avoided the site.”

This past May, when I happened to be in Lower Manhattan with some time to kill, perhaps out of an odd sense of duty, my professional museum background and a bit of curiosity, I decided to pay the $33 to enter the museum (there is no discount for New Yorkers, NYPD and FYPD pay $16, free for the military).

Entering the museum is not dissimilar to entering security at an airport or federal building: metal detectors, processed by security guards that scan every visitor with an unfriendly gaze. To those of us who remember flying commercially in the pre-9/11 world, the museum’s entrance process in it of itself is a reminder that 9/11, single-handedly and forever, transformed airport security worldwide (back then, while there were metal detectors, anyone could accompany their family or friends to the gate without a ticket).

After that initial filter, an escalator takes you down into the darkened depths of the museum— an experience that evoked in my mind the terrifying words of Dante from Canto III: "Per me si va ne la città dolente, per me si va ne l'etterno dolore, per me si va tra la perduta gente.” The connection is indirectly reinforced by encountering a quote by Dante’s guide, Virgil, at the bottom of the stairs: “No Day Shall Erase You From the Memory of Time.”

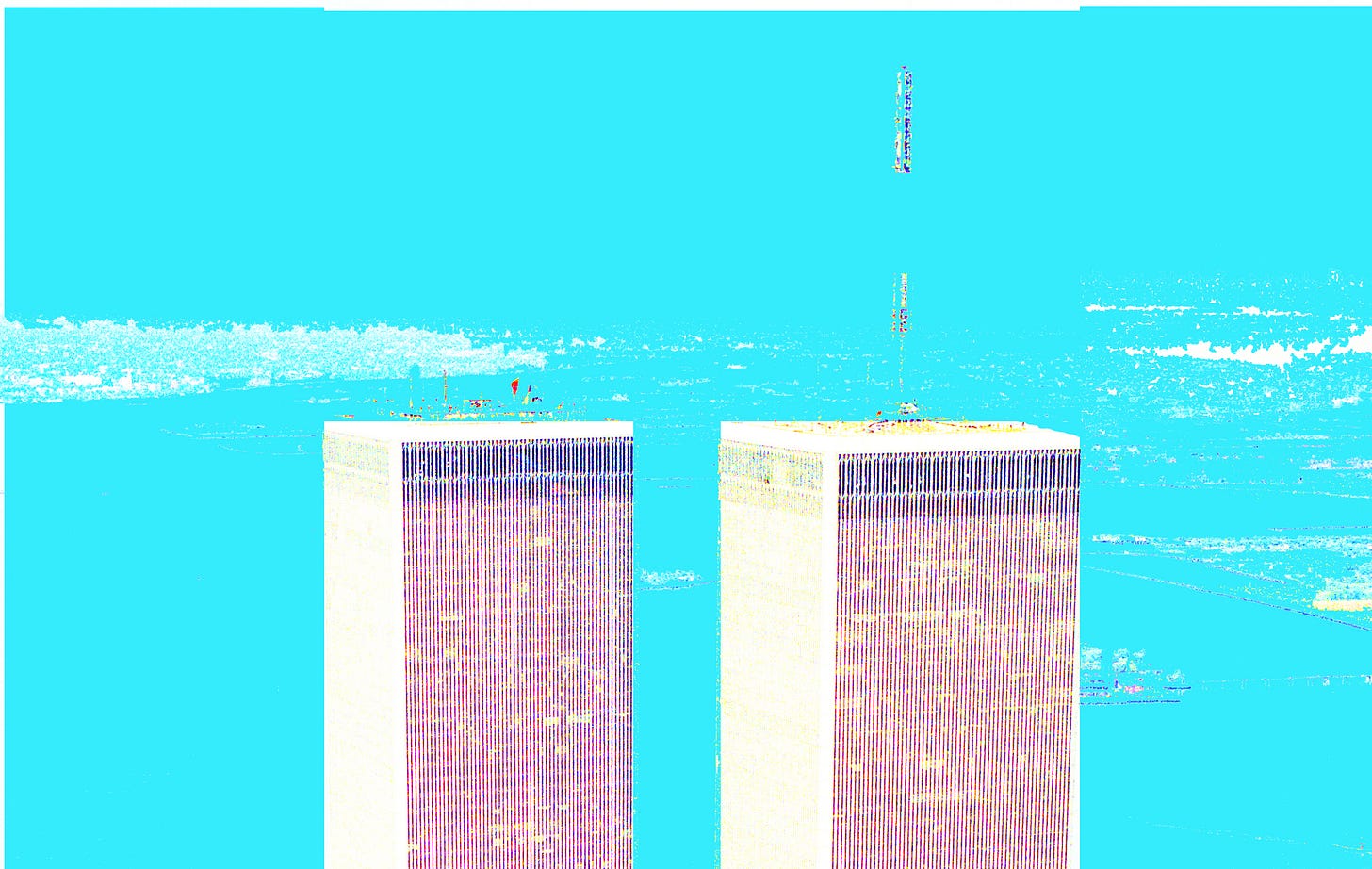

After encountering the last standing column of the World Trade Center as well as a section of the steel façade of the North Tower, one enters into an exhibit that narrates, minute by minute, the events of that fateful day, from the boarding of the planes to their crashing into the towers, their collapse, and the ensuing aftermath. The contemporaneous images, news reports and objects in the exhibition are overwhelming. Reliving the trauma, I found myself in tears in the middle of the museum, mostly surrounded by tourists for whom the story is more remote in space and time.

What I also was keenly aware about — as a former museum educator, I can’t help it— was that while the security at the museum is ubiquitous and extensive, there was not a single welcoming face, a sympathetic museum representative who would help me make sense of my grief. Only stern, suspicious and disapproving looks. The 9/11 museum offers guided tours, but to register you need to pay $53; a tour of the Memorial and museum is $84.

As I continued walking in penumbra onto another exhibit I encountered a film about Al Qaeda. Whether it is the same version or not (I was unable to corroborate it) of the 2014 film The Rise of Al Qaeda, presented when the museum first opened, I recalled that film caused great controversy because of its characterization of Islam and Muslims.

Watching that film I had a flashback to 2006, when I and Dannielle visited the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum. In a very similar way, the museum had a permanent exhibit describing, minute by minute, the bombing took place in April of 1995 at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, perpetrated by white supremacists Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, including a room with a horrifying real-time recording of a routine board meeting taking place just seconds before the explosion. However, the most salient aspect of that museum was an adjacent exhibit focusing on “The War on Terror” (unsurprisingly, given that this was during the Bush administration and only three years after the US invasion of Iraq). I remember feeling incensed by the emotional manipulation inherent in causing such great grief to visitors and then presenting a transparently propagandistic justification of the Bush doctrine.

By coincidence, a few months after my visit I was contacted by filmmakers Steven Rosenbaum and Pamela Yoder, who filmed 500 hours of footage of the immediate aftermath of 9/11 —the most extensive video material anywhere of that event— and donated the archive to the 9/11 Museum. Describing themselves as “accidental archivists”, they are the single largest donors to the museum’s video collection. They have the desire to further the conversation of how the museum could better serve the public and invited a number of scholars, museum professionals and Muslim community leaders to offer ideas and function as a community advisory council (this week Rosenbaum published an open letter stating the council’s goals and mission).

A small meeting was organized for this group to meet with both the 9/11 Museum’s president and its current director. While cordial, the meeting was clearly a courtesy extended to us so that we could speak our piece.

The most powerful statements at the meeing came from Muslim women leaders. One of them was Daisy Khan, Founder and Executive Director of the Women’s Islamic Initiative in Spirituality and Equality. Khan, who worked in the 1990s in the 106th floor of the World Trade Center and whose ex-husband is an Imam of a mosque originally located in Tribeca, was intimately impacted by the events of that day. Khan discussed how in the initial stages of the planning of the 9/11 museum, the director of the Newark Museum convened a group of other museum professionals and spiritual leaders to take a look at the initial storyboard of the exhibits. “It seemed as if the whole concept of the museum was about who did the attacks and why”— Khan later elaborated with me in conversation about her remarks at that meeting. “Watching that, I felt that we were again amplifying Al Qaeda and giving it more visibility.” But Khan’s primary concerns, which were also shared by other Muslim women leaders, had to do with the absence of the Muslim-American experience and their response. It is not only that 60 Muslims who worked at the World Trade Center were among the victims of the terrorist attacks, but that the museum, in her view, does not do enough to draw the distinction between Al Qaeda and the Muslim world. “Al Qaeda is an aberration; it is not rooted in Islam”— Khan told me, adding: “we are very quick to make a distinction between white supremacy and white people but when it comes to Islam that distinction is not done.” She concludes: “they could also show what is the lived experience of Muslims, and how communities responded, which is also part of the educational mission.”

At the advisory meeting, we mentioned how New Yorkers do not want to attend the museum. To which the museum director retorted that New Yorkers also do not visit other city’s landmarks like the Statue of Liberty or the Empire State Building. Many of us in the group were left speechless: how can anyone equate the visiting motivations between a tourist landmark like the Statue of Liberty and a site where 3,000 individuals had been massacred?

I left that meeting disheartened, full of questions, wanting to understand the nature of the problem with this institution.

A central obstacle that the 9/11 museum’s curators and educators face is the very inability to make a compelling case for its existence to the very constituency whose lives were most affected by the events it documents. In fairness to those who work there, this is a herculean task: New Yorkers, a group that is mostly about pushing forward and competitively into the future, are particularly averse at the idea of the contemplation of the past— especially if that past is traumatic.

But there is a political and pedagogical problem too. The understanding of the causes for the attacks requires a nuanced discussion of US foreign policy and involvement in the Middle East for the last 50 years without which these attacks feel as if they were coming out of nowhere. But this type of reflection is difficult to do in a public environment like a museum and it would risk to quickly be condemned as anti-American. Notwithstanding, what cannot happen is to replace discussion with silence. We must broker an inclusive conversation with the public — New Yorkers, the Muslim community, international visitors— about these issues. The alternative is that the vacuum is filled by extremism and hate.

9/11 changed my life in important ways. I wrote an essay at the time to make sense of what could art do to engage in the world at the beginning of the 21st century, and how we could break from cultural alienation. 9/11 is the single event that prompted me to pursue more active forms of participatory art which we now call social practice. In contrast to most of my friends, I believe we must have a 9/11 museum; however the museum’s philosophical premises, mission, objectives and strategies need to be radically rethought and clarified so that it does not merely remain as a triggering site for locals and a profitable selfie magnet for tourists.

The one thing that most agree on is that the memorial is meaningful. Tom Finkelpearl best put it: “given the fraught nature of everything related to the memory of 9/11, maybe the best opportunity is in the artwork (fountain/memorial). And the designer Michael Arad delivered a first rate piece of memorial art. It is a site of contemplation and mourning without bring jingoistic. I have visited perhaps 100 times because I live nearby. And it really slows people down in a way I find profound.”

All of which made me think again of that essay I wrote 22 years ago. Given that sometimes art works can produce understanding that can’t be achieved in other disciplines, a thoughtful art program for the 9/11 museum could help broker much needed reflection. It could play a role in assuaging that seemingly infinite void, caused by those events, within us.

Pablo - so powerful, these words. The memories, the impact, and the places where the Museum tears at the fabric of New York. Thank you. And, just to ratify your concern, the film you watched "The Rise of Al Qaeda" is the same film that was controversial back in 2014. Despite calls for it's script to be reviewed - including a request at the meeting with the new President and CEO, there was an unequivocal statement that a review was not possible.

Thsnk you, Pablo, for directing your always thoughtful insights to the question of 9/11 and its lingering effects for New Yorkers and the need for a museum that plumbs the effects on those most intimately affected by that day. As a New Yorker working at the Corcoran College of Art + Design in DC at the time, the experience was very similar for those in DC. I noticed it first in the reaction of the students. The Corcoran was (and still is, though now another institution) across the street from the grounds of the White House. As soon as communication was possible after 11th, I reached out to friends and colleagues at Parsons and Cooper, the two art schools closest to the World Trade Center, to make sure they were safe. We stayed in close touch in the aftermath and noticed the same thing. Not surprisingly, our students were so profoundly affected by the direct experience they were not able to make work about it. In contrast, students from art colleges around the country quickly began making work that incorporated visual symbols and text about the attacks. Our students were initially baffled that others would assume ownership of an experience they had only observed through mediation. There was one exception. The 11th was the first meeting of a new program in photojournalism. Unbeknownst to me, the students in that class evacuated the building, and instead of going directly to housing or home as instructed, they walked across the bridge to Virginia and took the first shots of the Pentagon. Many of those photographs are now in the Library of Congress. I bring this up because the immediate and collective reaction of these students was to act in the confusion of the attack in a way they understood. However, months later when the LoC asked for their work to join the collection, most students were reticent to share the work, possibly for the same reasons their cohorts did not make work about the events in the months after. Finding a meaningful commemoration is difficult, both personally and publicly. It is still worth pursuing a recognition of the complex reactions and spirit of caring for others that briefly characterized the days after the attacks.