Dogs look like their owners, they say— some even argue it is a scientific fact. Inspired in that theory I have recently been thinking about the extent to which we artists, consciously or not, resemble not our pets but our respective governments.

In 1989, when I first left Mexico to study in the United States, it took me several years before I could first return, primarily due to financial reasons. When I finally went back to visit , in the early 90s, the country had already begun a substantial transformation due to the introduction of the North American Free Trade Agreement and other related neoliberal economic policy changes made during the presidency of Carlos Salinas de Gortari. I was struck by how things looked different, shinier, supposedly because the country had become “modernized” — which in practical terms meant that US businesses had started their expansion into Mexico. I had a Rip Van Winkle sensation— the feeling that I had missed an entire chapter in the history of my country. This odd experience is one of temporal disconnect, which means that when one returns to the place where time has elapsed, one continues where one left off time-wise. So I was mentally resuming my life as I had left it in August 1989 while everyone else had moved on. I started noticing this discrepancy when I went out to lunch with an ex-high school friend who started making fun of my verbal expressions and gestures. “You are totally antiquated!” she told me laughing. There were new (albeit implicit) verbal and physical codes in fashion amidst our generation, all of which I had missed. It’s a peculiar but perennial phenomenon with immigrants: when you emigrate, your language and cultural expressions become frozen in amber, while in your place of origin they continue evolving (my sisters, who also emigrated to the US in the 1980s still share with me the Mexico City slang that was in vogue during that period but not anymore).

However, the interesting aspect of suddenly being an outsider in what used to be my community was that I also became more aware of the cultural codes (semantic, gestural, ritualistic, and so forth) that governed it: upon my more frequent returns to Mexico, I started noticing not my own language (which was incrementally becoming contaminated by anglicisms and English syntax) but the language of Mexican artists and intellectuals, particularly the one used in public and academic contexts, such as publications and panel discussions (of which I have organized countless amounts): sometimes they vaguely shared similar rhetorical flourishes and protocols of political discourse, even a few PR rituals that up to my departure felt totally normal (like having a local politician “inaugurate” an art exhibit with a vacuous speech). I had undergone a grueling training to learn how to properly write in English and specifically follow the basic tenets of essay-writing, things like directness instead of metaphorical richness and clarity instead of the poetic ambiguity that I was accustomed to. It was a confrontation of cultural values, one of which translators have to be very aware of. But there was something more: the formality of the language started reminding me, of all things, of the baroque quality of political and bureaucratic discourse- the emphasis of form over content, if you will. Old-school cultural determinists would make a connection between the Protestant austerity and the Mannerism of the Counter-reformation in this divide. I am not willing to go as far, but over the years I still could not help but notice how the political climate does appear to influence the artistic climate, in ways big and small. Was it a direct causation, or did both originate from their shared cultural roots?

Jerry Saltz made me think of it first back in 2004 when he argued that John Currin was “the perfect artist for this administration” (i.e.. the W. Bush administration), adding, “he is a compassionate conservative” which, humor aside, I think it is very true.

To clarify , the relationship between art making and institituionality that interests me the most is not the historically common instance where artists become the official spokespersons, apologists, and/or propagandists of a political system (i.e.. the “official artists” of a regime) but the ways in which they adopt or are influence by its language, whether consciously (as a critical stance) or unconsciously (adopting common demeanors and arguments even if it is against that very system that influences them). The influence operates, I would theorize, by adopting the permission structures created by those in power. By permission structures I refer to how certain behaviors (lying, or outright confrontation of the public) can become acceptable under environments where those same actions have been normalized, although not presented as art. But if one thinks about it, how can we not see the history of political and activist art as a turning of the tables when the artist speaks truth to power? That might be a topic for a cultural psychologist to unpack.

On the category of deliberate appropriation, which is much easier to chart, an artist who has actively sought to incorporate government-speak as art in Mexico, by means of conceptual poetry, is Vicente Razo. Razo is a conceptual artist who first gained notoriety in the mid 1990s when he created El museo Salinas, a project consisting in the collection of all the many handmade folk objects, masks, and toys made by local Mexican artisans to ridicule and protest the neoliberal regime of Mexican ex-president Carlos Salinas de Gortari (precisely the one who brought NAFTA into effect) with all the economic woes that he brought to the country.

Razo’s museum was one of the few projects in Mexico that directly aligned with the postmodern institutional critique debates that were currency in the art world then, made only a few years after Fred Wilson’s “Mining the Museum”, albeit in his case utilizing true Mexican humor and celebrating Mexican popular ingenuity in the process.

The project of Razo that comes to mind in relation to governmental language are his “Jornadas de Poesía Administrativa” ( Sessions of Administrative Poetry). His project initiated in 2014, as part of an important exhibition and multi-faceted research project organized by Sofía Olascoaga in Cuernavaca entitled “Entre Utopía y Desencanto”, which sought to explore the radical ideas about collectivity as well as the experimental approaches in art, psychology and sociology that took place during the decades of the 1950s-80s in that city.

Razo chose to organize a poetry-like reading of the actas notariales (i.e.. the articles of incorporation and bylaws) of the creation of the CIDOC (Centro Intercultural de Documentación), a research and learning organization created in Cuernavaca by the thinker Ivan Illich with the mission to train missionaries and educators. Razo did not intend to make a critique of Illich, but rather, as he told me, “I was interested in these acts as documents that demonstrate the inevitable, contradictory and almost always devastating encounter between utopia and bureaucracy that is needed to survive, and I thought of two things: first, that this is something that many artists have to face and deal with, and second, that it would be incredibly boring to read these documents aloud. And as result of this we presented the first Festival of Administrative Poetry, an event that was kind of a combination of trance, torture, purge and therapy that in the end turned out not to be that boring.” Other artists that Razo invited to read administrative poetry included Luis Felipe Fabre “who read his interminable and Kafkaesque correspondence with the Cervantino Festival [an international arts festival in Guanajuato, Mexico] in order to get paid for a presentation he gave —if I recall it did not have a happy ending—; Mario Ybarra Jr. read a bizarre eviction notice from his studio written by a landlord with feudal delusions” and also “Miguel Ángel Camacho read, in a meticulous and monotonous way, a collection of gas receipts of his father who is a cab driver, where the increment of the prices appears very slowly— it was a reading that made the audience very impatient.”

Razo thus proved that Latin America is a very fertile ground for administrative poetry. As I tried to argue in a small (and of course, satirical) book published in 2009 and titled “Hacia una Estética de la Burocracia” (Toward an Aesthetics of Bureaucracy), if one were to use bureaucracy as the basis of a conceptual strategy, Latin America would surely prove to be at the forefront as its most radical practitioner.

Furthermore in this project, just as in his Salinas Museum, Razo was again sensing and/or engaging in a current international literary/artistic conversation, this one which had become the rage by the early 2010s: conceptual poetry, a genre that Marjorie Perloff best studied and documented in her book Unoriginal Genius- one that draws both from Duchamp and Brazilian concrete poetry, creating a late version of poetics of appropriation. The conceptual poet Vanessa Place, who is also a professional criminal appellate attorney, is a leading figure in this form of writing— one who has often used her own appellate briefs and courtroom materials for her work. And of course another prime practitioner of this approach that he has himself dubbed as “Uncreative writing” is Kenny Goldsmith. Goldsmith himself has made incursions in government materials, most notably the work he did in 2019 at the Venice Biennial where he printed and exhibited all of Hillary Clinton’s emails. Even more notable than the piece itself, perhaps, was the fact that the former Secretary of State and presidential candidate actually visit the exhibit, and loved it.

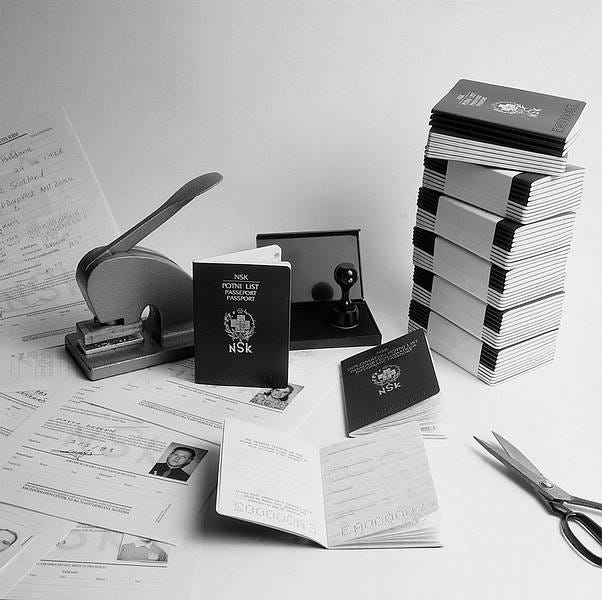

Another great example of bureaucracy as form is the Slovenian collective IRWIN’s NSK Embassy, one of the collective’s most celebrated projects. The NSK Embassy expedites passports for the fictional NSK state, using the similar bureaucratic antics of the pre-Balkan war states, with loads of paperwork, rubber stamps and official-looking seals. We organized a brief section of the NSK Embassy at MoMA in 2012 in conjunction with the exhibition Print/Out.

The list is so vast that we could certainly have a biennial exclusively about bureaucratic discourse, where the theory put forth here ( i.e. artists resembling, or at least impersonating, their governments) could be put to the test. There is of course, the inverse type of practice, no less fascinating: how politicians resemble artists. But I will leave that for next week.