Reply All

Art imitates email— and vice versa.

My 13 year-old daughter does not use email. When I asked her why that is, she replied: “It doesn’t work. You say ‘hi’ to someone and it takes a day for them to respond.” Instead, for her generation, Snapchat and texting reign— the obvious point here being that the expectations of immediacy in today’s communications make emails feel like dinosaurs, which makes someone like me, who started their professional life right around the widespread use of email, also a dinosaur. But as I reflect on my own obsolescence, I have been considering how, like other outmoded things I often write about (35mm slides, business cards, etc.) emails also deserve a bit of praise of their own as the ugly ducklings of 21st century communication.

First, while email might be seen as ancient technology the routine reports of its demise have been greatly exaggerated. It continues to be the dominant method of office communication. Today, there are 4.5 billion email accounts in the world, approximately one per every two living humans on the planet. That likely includes you: if you are subscribed to this column you are receiving this via email.

Still emails, like painting, are often (and unfairly) declared dead. But in contrast to painting, besides not being a formal art medium, email has never been all that interesting to make art with: we never had the equivalent of a rich “Mail Art” movement, or genre, with email. Of course, there are exceptions, as I will explain further. But first it might be helpful to review the life story of email and its initial, non-creative uses in the art world, such as connecting, discussing, networking and promoting, with the thrill and the mortification that accompanies the power of instantly reaching large groups of people.

The novelty of email when it started as well as the relative scarcity of emails one would receive, somewhat obscures the memory of when group emails did not feel like spam; yet spam precedes the internet itself. According to email historians, the first spam email was sent on May 1st, 1978 shortly after the creation of Arpanet — the predecessor of the internet— and it was universally disliked — but at the same time, like all advertising, the point is not to be adored but to get a message across.

I recall emails by over-eager, self-promotional artists who would send enormous descriptions of the many projects they were doing to prove how busy they were, later soliciting me for invitations to come lecture or exhibit at the museum where I was working (which made me wonder: if they are so busy, how come they have the time to send me such extensive emails outlining their many projects?) Other emails were like personal chronicles in the art world. I recall the ones from late curator Victor Zamudio-Taylor. Victor was simultaneously brilliant and at times troubled, a hyper-active thinker and art world gadfly whose self-promotional persona never bothered me, perhaps because it was so deftly integrated to his wit and balanced by his generous attention to his interlocutors. Often writing in all caps, he would always put the city he was in and the date in the heading of his emails as if writing an old-fashioned letter (which I enjoyed). He always sounded as if he was in a hurry, having to be in 20 different cities per month and having to attend every single important art event occurring in them.

Email, of course, soon after its widespread use gave us an initial exposure to the potential risks inherent in the benefit of contacting huge amounts of people at the stroke of “send” (like the subsequent “post” in social media).

When I started working in museums in the early 90s we all still communicated by hard copy memos placed in people’s mailboxes but then we transitioned to email in the mid-90s — the MET being one of the very last ones to join that system). There were growing pains. Sometime around 1999 a curator at the Guggenheim – let’s call him Ethan Becker— set up a vacation auto-response that, also inadvertently, would Reply All whenever it would receive an All Staff announcement (a likely flaw not just of Becker but of the whole museum’s email system). Since we often received a few All Staff emails every day, we would all immediately receive Ethan’s response. “Thanks for contacting Ethan Becker. I am on vacation. I will get back to you when I return.” This went on for a couple days, until another staffer sent another All Staff email: “Does anyone know where Ethan Becker is? Is he on vacation? Does he know how to use his Out of Office feature?” After which we all of course got Ethan’s response again, like a Baroque coda: “Thanks for contacting Ethan Becker. I am on vacation. I will get back to you when I return.”

You would think that after two decades or so of email management maturity we would have outgrown such risks, but human error seems to ensure that we can’t always prevent such mishaps. A few years back my email was part of a NYU listserv of Latin American art, which would regularly send announcements of exhibitions, events and publications—with all recipients, I should note, put on the cc section, a major no-no in standard email list management practice. The emails were sent out by a student assistant whose name would often appear as sender— let’s call her Luisa. On one occasion, one of Luisa’s professors, who obviously was also part of the list, send her a reply, not realizing that she was emailing all recipients. “Luisa”, the email approximately read; “you have not submitted your final papr [sic] and should you not do so by the end of the week you will be failing the course.” The email went on and on to chide poor Luisa for neglecting her responsibilities in class. Shortly after that the great Luis Camnitzer, who like me was on the listserv and realized that it was not protected against the “reply all” feature from recipients, sent an email directed to the professor (and us all), approximately saying the following: “I am not sure if you realize that you have just emailed all the art professionals in Latin America. Your typo-ridden message, as well as our incompetence at not realizing that you are sending a mass email makes me doubt of your ability to properly model responsibility and professionalism for this student.”

Thinking back, I have been reflecting on how artists of my generation instinctively tried to construct our messages by using email, both in practical and artistic terms. I recall a famous artist of my generation, when I would ask him how he was doing he would answer, “I spend all day sending emails”, to which I understood to mean “ being in touch with and sending proposals to curators”. I personally got one of my first shows in Europe because of email—sending an out of the blue message to a curator that turned into a back and forth correspondence that eventually turned into an invitation. But for me email was primarily about conversation and content generation. One of the first emails I ever sent was in 1995, when I was living in Barcelona and was invited to submit a travel piece about the city “via modem” to the Chicago Tribune ( a modem that the paper itself had lent me to submit the piece to them). It was a magical experience to have them receive it. Later I became part of debates organized by Universes-in-Universe, one of the first contemporary art publications on the web created by Gerhard Haupt and Pat Binder in Berlin, including those sparked by José Roca’s Columna de Arena, an email newsletter that discussed art in Colombia but which led on quite a number of open forum debates around curating and beyond, all of which many of us contributed with comments sent via email. Shortly after that, the e-flux era began.

But back to art made with email: the excitement it generated contrasted somewhat with how we saw its limitations in what could do for visual artists, but as with anything there were a few imaginative exceptions (the very term “net art” was coined in 1995 by Slovenian artist Vuk Cosic when he opened an email that had been corrupted in transmission, with only one legible term “net.art”, which he then employed to talk about online art and new media).

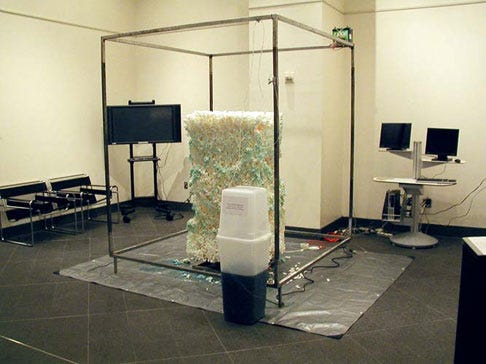

I think of artist Ethan Ham’s Email Erosion from 2006, a piece commissioned by Rhizome, which fed from spam email to build a foam sculpture. But even then, the piece is not so much a work about email per se as it is a harnessing of the data received by the mechanism of email to produce a piece through a preset algorithm— in a certain way, a precursor to Refik Anadol’s crowd-pleasing Unsupervised at MoMA.

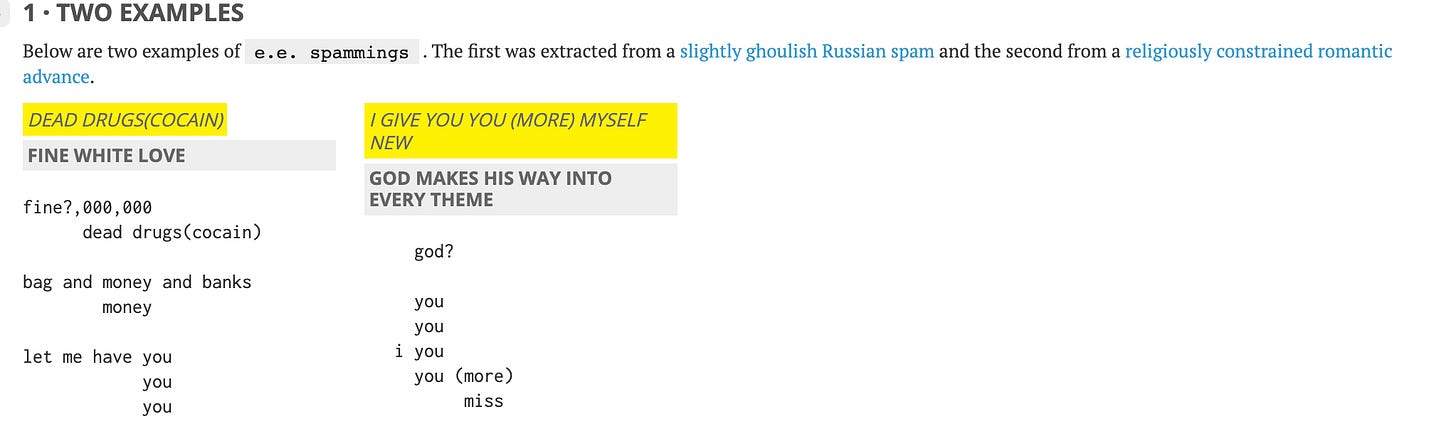

Because of its very own nature, email has been a much more fertile ground for writers than for visual artists. Some might recall the short-lived Flarf poetry movement, a conceptual poetry approach which mined the internet and emails to create poetic works. Related to this movement was Spam Poetry, which used recycled spam messages. A leading practitioner in the field was the Canadian artist and scientist Martin Krzywinski, who published a number of poems that he titled the e.e. spammings project with the statement: “The world doesn't need more spam. But it needs more poetry. Given the excess of one and shortage of the other, I thought it would be useful to develop a process that turned spam into poetry. The e.e. spamming project recycles spam into poetry. The availability and permanence of spam suggests that this is a sustainable effort.”

I have written in the past about Kenny Goldsmith’s project consisting in printing all of Hillary Clinton’s emails. Yet another of my favorite conceptual poets who has used online language communication (not necessarily email, but the colloquialisms of the era that also include social media) is Rob Fitterman. His book Now We Are Friends is, in Fitterman’s own words, “a social media version of Acconci's following piece--I start by following one random person who had a strong internet presence and then followed his friends and friended his friends. It harvests more from FaceBook than straight up email, but it has the email vibe heavily.” In response to my question about why this kind of online written exchange interests him, Fitterman says: “ can found language be subjective, emotional, even personal? Yes, I would argue—it can be utilized as a public chorus.”

Thierry de Duve, in a series of essays in Artforum back in 2018 (“Don’t Shoot the Messenger”) characterizes the story of the avant-garde as a process of correspondence, starting with a “message” sent by Marcel Duchamp, later answered by a number of artists in subsequent decades. If one is to extend this message metaphor to email, I might dare to add that every art work, in a sense, is a “reply all” email, engaging with the “public chorus” that Fitterman describes.

As we complete the first quarter of the 21st century we have the privilege— or the misfortune, depending how you want to see it— of working on the edge of virality, where every artist will be famous for the fifteen seconds that takes to read a meme. Which may allow us to make another case for the intimacy of email, which is a message sent to only one person furthering a unique and unrepeatable exchange— except, of course, if our email is to land in the spam folder.

Judith Ren-Lay here reading you with appreciation and interest as always.

I believe I sent you a copy of my book Quartet - four-part harmony from a recollected life?

Book 4 - Accidental Grit is primarily comprised of emails I sent after I had been hit by a cab in 2011 fracturing both legs requiring years of rehab to learn to walk again. Those emails saved my life and became a featured element in what I consider my latest work. Just another example of this now ignored form you write about this week.

All the best,

Judith Ren-Lay