Sawdust Tears of Reading Pleasure

The sentimental journeys of a used Spanish-language bookstore.

This weekend we celebrate the 10th anniversary of the creation of Librería Donceles— a socially engaged art project launched in New York in 2013, now at the Mitchell Museum in Annapolis, Maryland.

One of my earliest childhood memories, in Mexico City —circa 1975— involves being with my father in his office in the lower level of the house we had on Orizaba Street in Colonia Roma. I would ask him to show me “el libro de las cabezas” (“the book of the heads”). He would pull out a massive 2 leather-bound set detailing the history of the Crusades, a Spanish-language edition printed in 1887 of a 1840s history written by M. Michaud and profusely illustrated by Gustave Doré. The engravings —just like the ones he made for Dante’s Divine Comedy— showed both the artist’s incredible draftsmanship and the way he seemingly reveled in depicting gruesome scenes— in particular images of decapitation, such as a depiction of the Crusaders throwing heads onto the streets of Nicaea— which was what prompted my descriptor of the book.

Like almost any other Mexican 4 year-old I also listened to Cri-Cri, the legendary children song composer, active for seven decades. One of his most famous songs is La Muñeca Fea (The Ugly Doll), about a forlorn, raggedy doll that has now been abandoned by her owner in a dark corner. I was deeply moved as a kid by hearing the story of how a mouse comforts the doll by telling her that she is not alone, but that her friends, which include the broom and the duster, as well as the mouse himself, are there for her.

In the song, a line goes:

Y al sentirse olvidada lloró,

Lagrimitas de asserrín.

And feeling forgotten she cried,

Sawdust tears.

Years later, the topic of books and abandonment would come together for me.

I always say that I belong to the last analog generation— those of us who grew up without internet. The way to do research for assignments was to resort to whatever encyclopedia we had at home. The one we had was an encyclopedia Barsa (once I had to do research on Assyria (the ancient civilization), and instead copied a whole article about Syria -the country- which got me a failing grade). But my relationship with the books was intense and deep: we had the inherited library of my grandfather, a businessman who late in life wanted to become an author and acquired full collections of books by French imprint La Pléiade, the Argentinian Colección Austral (all the titles available circa 1941) and every title from Mexican literature of the period.

As a teenager I felt a powerful sense of urgency to know it all. Somehow buying books was the way to do it in my mind, but it was hard, given that I had little money to acquire them. So as soon as I was allowed to go around the city alone I would go downtown Mexico City to explore every museum and historical site (in retrospect, this is also why I have always psychologically associated learning with nomadism: I was a hunter-gatherer of knowledge). But primarily I would go downtown to buy cheap books.

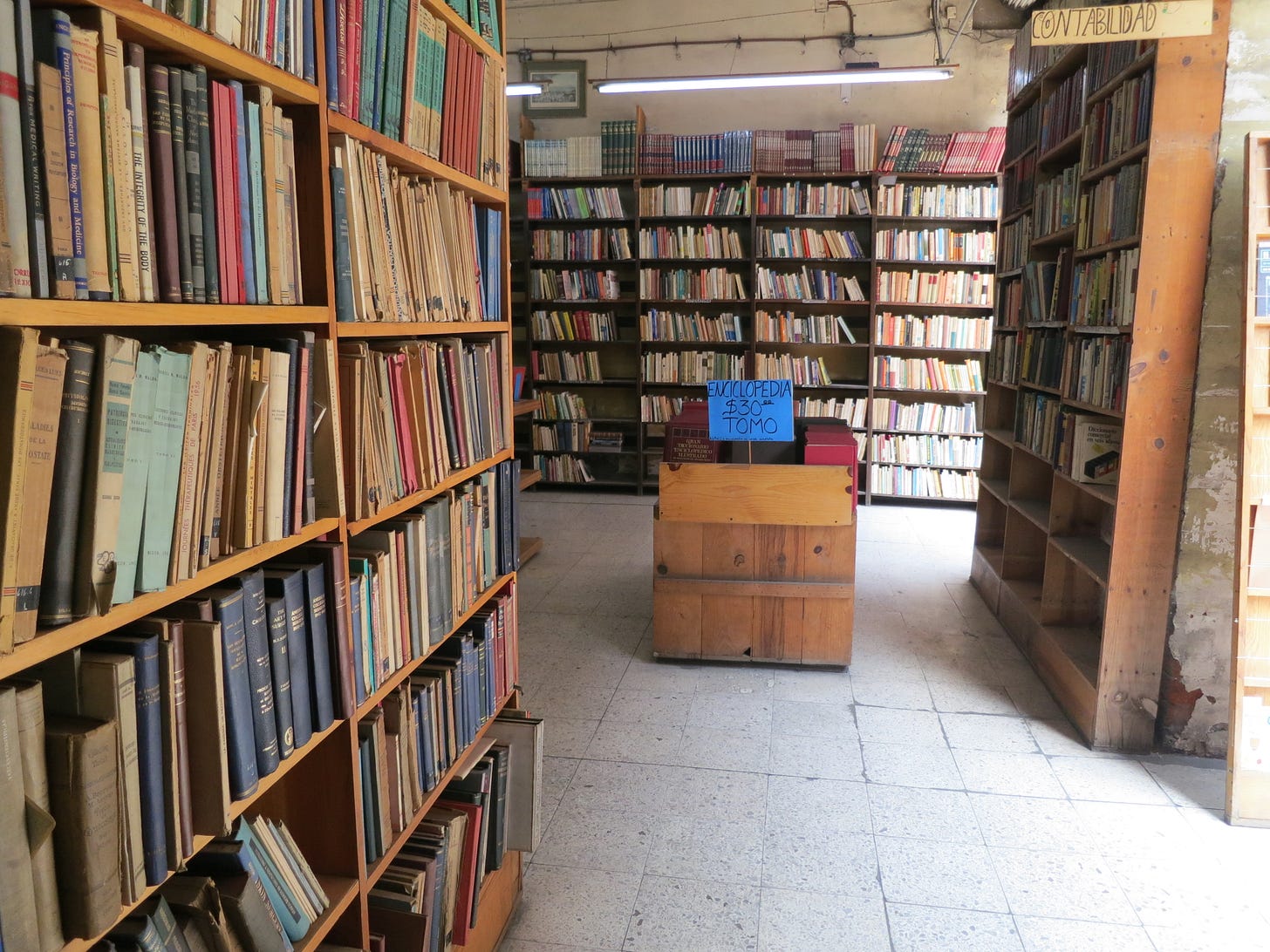

In downtown Mexico City, there is seemingly a street for every kind of business: callejón Girón is where you go to buy children’s toys, República de Chile is for wedding and quinceañera supplies, Madero is for jewelry, Granaditas for shoes. But if what you want is used books, you have to go to Calle Donceles.

Donceles Street is not far from where the first printing press of the Americas was established, in 1539, thanks to the the first bishop of Mexico, Fray Juan de Zumárraga, who brought an Italian printer from Spain named Giovanni Paoli, later known as Juan Pablos.

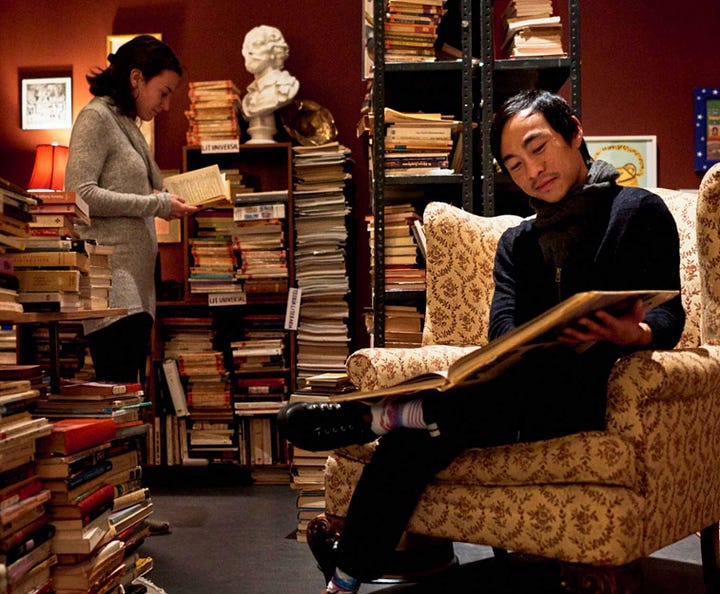

The used bookstores in Donceles —many of which still survive— were chaotic and messy, sometimes organized haphazardly and more in piles than in neat stacks. But they were cheap and plentiful, and I really cherished the experience of getting lost in those tunnels of books, like a gold-digger, to pull out a small gem every now and then. The obscurer the book I found the more I felt that I was attaining a special knowledge that few, if any, shared.

Years later, when I went to art school in Chicago, I felt something was missing. The classes available to me were mainly art history and art technique, but I actually wanted to learn ideas. I would be on the phone with my high school friend Carlos Aizenman, who like me had come to the US to study, but Carlos was at Brown, studying neuroscience, and was receiving a first-rate ivy league education, with a class on Western thought that I was really envious about. My sense of urgency and peripatetic learning kicked in high gear, and like I did in Mexico City I started searching for used bookstores to complement the gaps in my education.

I combed all the used bookstores in Chicago. The best ones were on Clark Avenue; where we lived (West Rogers Park) there were few. There was a small used bookstore with an eccentric old bookseller who dyed his hair black and had a bald spot that he attempted to cover with what looked like shoeshine.

My favorite go-to place was Bookman’s Alley in Evanston. Run by the late bookseller Roger Carlson for three decades, it was the quintessential idiosyncratic used bookstore. It felt like someone’s house —and the accumulation of books everywhere reminded me of the homes of writers from Mexico City: various nooks and crannies, peculiar rugs, little tables, lamps and sitting places, a soundtrack of music from the 1930s. There I purchased my first copy of The Waste Land, a 1900 edition of The Principles of Human Knowledge by Bishop Berkeley, books by Gaston Bachelard and Henri Bergson— basically the Western-dominant bibliographic references that I had learned from my brother. But while I was reading fairly traditional titles, I was still on the margins of knowledge, accessing ideas from half a century ago or more— not a great start for someone who wants to become a contemporary artist.

Fast forward to 2013 in New York. We were witnessing the demise of many brick-and-mortar bookstores (used and new) after the advent of eBooks. The last bookstore at that time that exclusively sold books in Spanish in New York, located on 14th Street had recently closed. It was striking to me that in a city with 2 million Latinx residents we would not have a Spanish-language bookstore. I also observed that the act of replacing the physical object of the book with a digital version throws away a central aspect of our relationship with it. When you purchase an e-book or a song for your music library, you are not really purchasing any tangible object but instead the right to reproduce/read it for as long as you have access to the platform that “sold” it to you. The commodity is not transferable to anyone else, just as you can’t just gift an app or a movie to someone else. In contrast, books can be resold, lent, or gifted again and again, which is a key legal category in the United States. As library expert Jennifer Jenkins points out, “The “first sale” doctrine (17 U.S.C. § 109(a)) gives the owners of copyrighted works the rights to sell, lend, or share their copies without having to obtain permission or pay fees. The copy becomes like any piece of physical property; you’ve purchased it, you own it. You cannot make copies and sell them—the copyright owner retains those rights. But the physical book is yours. First sale has long been important for libraries, as it allows them to lend books without legal hurdles.”

So when Douglas Walla from Kent Fine Art gallery in New York approached me about working together and doing an exhibition I told him I had a crazy idea that probably he would never accept. “Try me”, he replied.

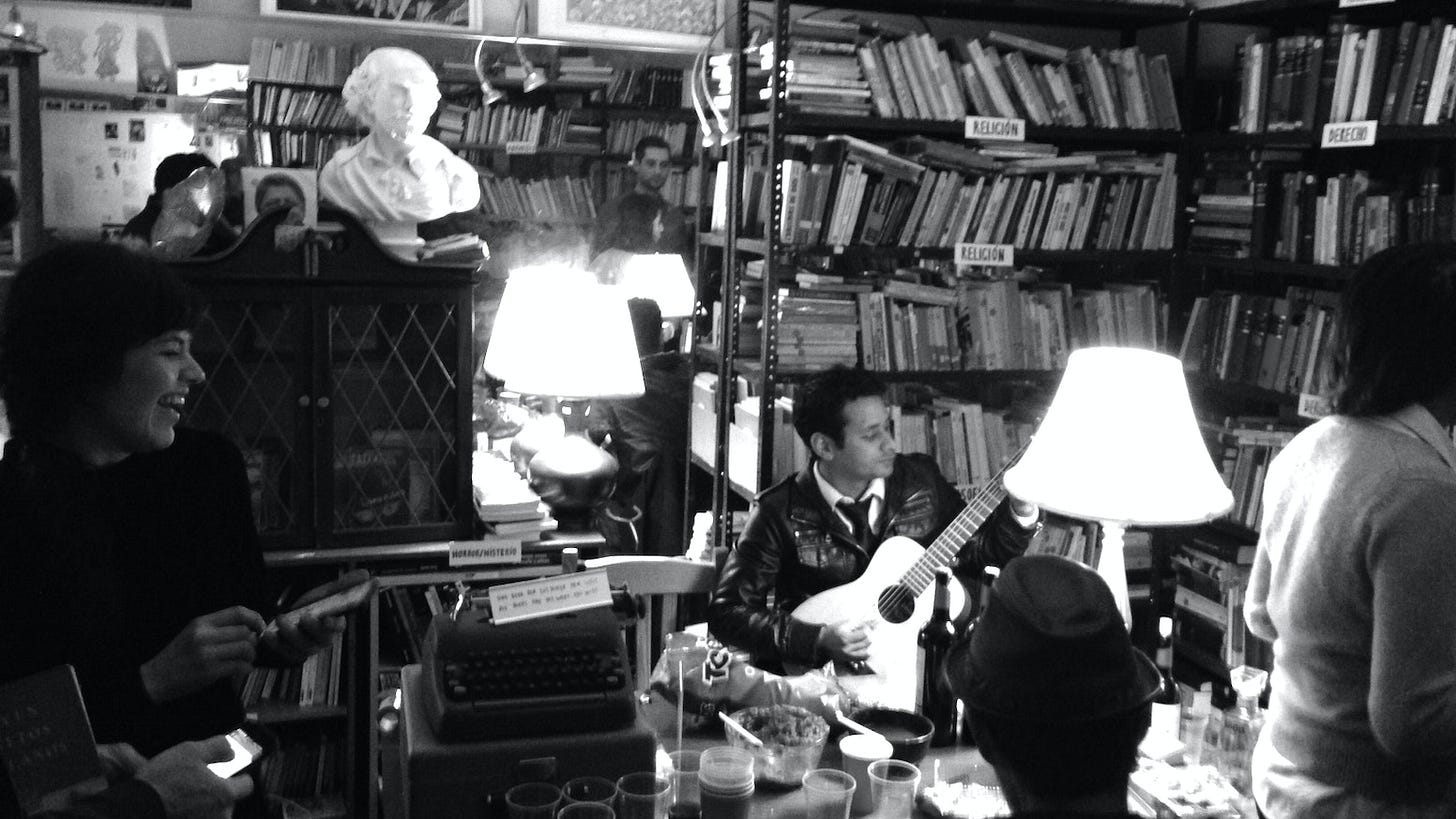

I explained that I wanted to turn his gallery into a used Spanish language bookstore— in essence, a failed business. He said yes.

A few months later I was in Mexico City, starting a campaign to get book donations. There are two facts about Chilangos (people like me, from Mexico City): one is that everyone is sympathetic of the plight of the Mexican immigrant; giving books to help immigrants reconnect with their roots felt like a small but meaningful gesture. The second fact is that in most middle-class households in Mexico City, since people don’t move often, accumulate lots of books— inherited from previous generations, schoolbooks that remain behind by grown children, and so forth; so practically every household has books to give. I started small, but the campaign took off after it was covered in the media, and then I started receiving books from everywhere, including other cities like Veracruz and Puebla, reaching close to 20,000 volumes. Just for reference, 20,000 volumes constitute about 450 large boxes of books.

When we opened the bookstore at Kent in September 2013, one of my central concerns was that we would run out of inventory in a few days. On the contrary, the bookstore attracted as many donations as it sold books (all proceeds go to a local Latinx cultural or educational organization). It also attracted invitations by organizations in other cities to host it. Ten years later, the bookstore has been in Manhattan and Brooklyn, Miami, Phoenix, San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago, Indianapolis, Boston, Anchorage, Santa Cruz, Los Angeles, and now in Annapolis, Maryland as we celebrate the bookstore’s 10th birthday.

Looking back, I can point to at least two main things that I learned about books—and incidentally, about myself— in this project.

The first thing (which I did not fully anticipate) was the deep personal emotional charge that books contain as objects. Practically every visitor who entered the bookstore — even if they were not a Spanish speaker— had a story about a book that had impacted their life, almost invariably a story that involved a family member, friend or teacher who had connected them with that object. Each book would be a vessel of sorts of the positive memories, sometimes connected to the very life of the visitor. There was a 97-year old Spanish woman in Indianapolis, who walked into the store and asked to purchase a book of the history of Spain, from which she had emigrated in her youth; there was another reader in New York who wept when finding the exact edition of a book that had been given to her by her grandmother and she had lost. There was the Julio Cortázar-obsessed visitor who came every day to the bookstore (the rule is pay-what-you-wish, but only one book per customer per visit) and took with him every Cortázar title we had available. And there were a group of women from Veracruz who contacted me to donate books. When the book arrived, I realized that the women had dedicated every single volume they donated to a future anonymous reader. It was a loving act of faith and generosity.

The second thing I discovered — and have only reflected upon in recent days— is how the search of hidden knowledge is, ultimately, a search for identity, particularly for those who don’t dominate the mainstream discourse. The brilliance and power of dominant ideas in art works has the effect of making the humbler artist feel lost, unable to grab onto a defining interest that they can truly call their own. I was a sixteen year old Mexican kid trying to define myself; I had little access to the great conversations of literature; instead I dug into obscure knowledge offered by the used bookstore; forgotten authors and titles that become precious partially because the potential of their rediscovery and revaluation. Like the ugly doll, these books— not with sawdust tears but often with the holes made by termites— have a chance to find new friends. And through us, the nerdy scavenging readers, they can speak again.

What a cool idea and beautiful reflections about what you've learned through the project. I'd love to visit! Is Annapolis the last stop or will it continue throughout other parts of the US?