From Marshall McLuhan to Jodi Dean, many media theorists agree on one fundamental point: whoever controls the images controls the masses. It’s hard not to feel disheartened to be part of the image-making field, at a time when the visual arts seem overshadowed by political propaganda, which wields a far more sophisticated understanding of the power of imagery from social media bots to memes and digital ads. Just today, my Facebook feed was overtaken by a slew of fake supermodel bots, all posting glowing stories about Elon Musk.

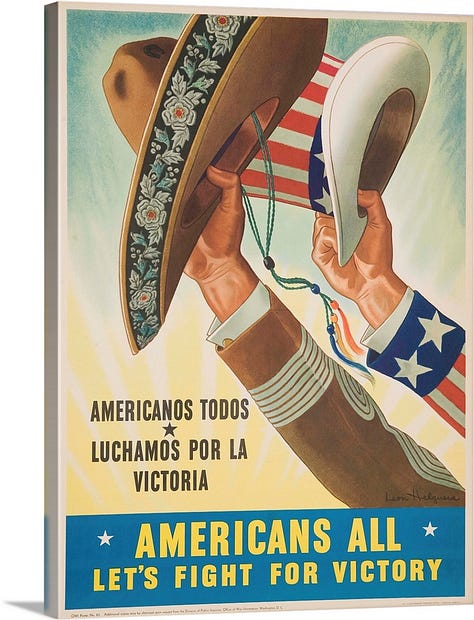

Amidst this reflection, I came across a propaganda image this past Saturday that harkened back to our collective past and my family's history.

On March 29th, The New York Times published an Op-Ed by Frank Kendall, former secretary of the Air Force under the Biden administration, who argued, “in the wake of signalgate,” that the current administration's actions, including the irresponsible use of communications, the dismissal of key military leaders and policy shifts, threaten the rule of law and U.S. national security.

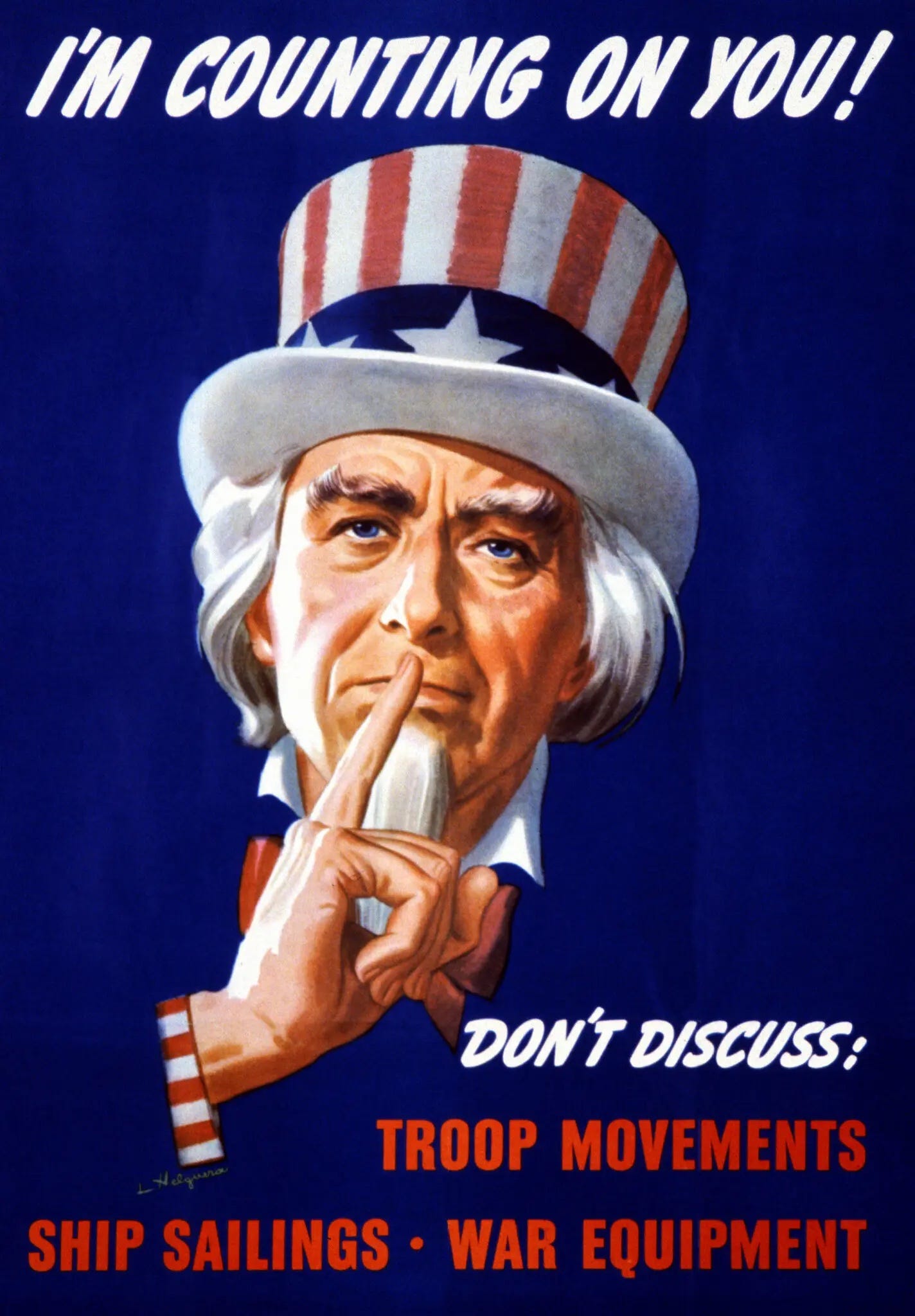

The illustration that the Times used, which did not credit the artist, is the famous Uncle Sam “shush” poster that was widely disseminated throughout the United States during World War II and became ubiquitous: in it, Uncle Sam holds a finger to his lips with the message “Don’t discuss Troop Movements • Ship sailings• War Equipment”. I want to correct that oversight today, and also mention that, for all its patriotism, this image was actually created by a Mexican artist who was working for the US government during the war: my grand-uncle, León Helguera.

León was born in 1899 in Mexico, the youngest of 7 siblings. We do not have a lot of details about his early years. My grandfather, Ignacio Helguera, perhaps the most enterprising of the siblings, emigrated to New York City in 1904 at age 15, soon after their parents had passed away. Around 1916 he brought his siblings to the United States, including León. I do not know if he ever received a formal academic art training, but by his early 20s he already was an accomplished draftsman.

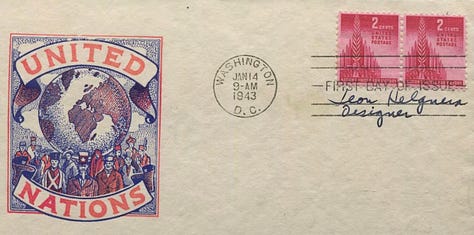

He is mostly remembered by the postage stamp collector community. He was one of the first artists ever employed by the United Nations, shortly after the 1942 declaration of the UN and even before its charter was ratified in 1945. He is well-known for the “United Nations” 2-cent stamp (1943), the U.S. 3-cent stamp commemorating the 300th Anniversary of New York City (1953), the 3-cent U.S. -Canada Friendship Issue (1947), among others.

In 1942, the Office of War Information (OWI) started an American version of the British “Careless Talk” campaign—one where the agency, along with the Office of Facts and Figures, (OFF) summoned Madison Avenue ad agencies to craft a messaging strategy for the American public. Slogans like "Loose Lips Sink Ships" became one of the best remembered phrases of that era (and particularly resonates now in the wake of Signalgate). As part of this initiative, OWI commissioned the “hushing” Uncle Sam propaganda war poster to illustrator Robert Sloan. Sloan’s image, however, did not sit well with the Chief of Graphic Division, Francis E. Brennan, who observed that Sloan’s Uncle Sam looked too much like general George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, a resemblance that felt controversial to them and which the artist later tried to address, unsuccessfully. In 1943 they turned to other artists to do the commission, including Norman Rockwell, who declined due to his busy schedule. Finally in April of 1943 they give assignment to Helguera, who agreed and delivered the work in two weeks.

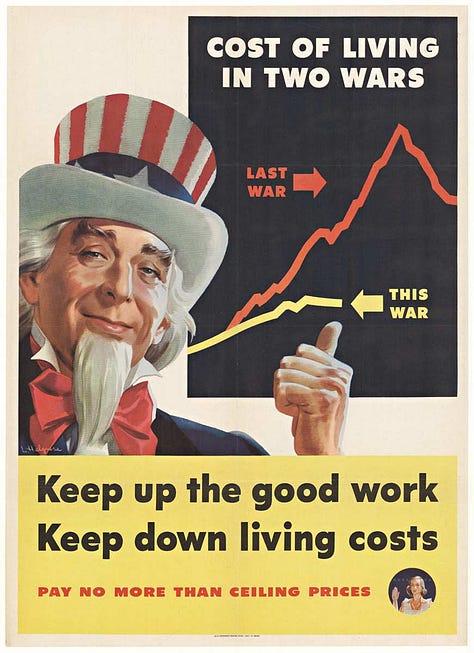

After the war, León continued working as professional illustrator (of particular interest to me is a poster he did about Pan-American cooperation). He returned to Mexico City around 1957, when my parents got married. He designed a number of postage stamps for the Mexican government and did various commissions. In order to support him, my father often commissioned portraits and watercolors to him, many of which we still own. He died in 1970.

Like my other artist uncle, the muralist Francisco Eppens Helguera, whom I wrote about a few years back, León did not appear to have a clear ideological stance—if he did, he left no record of it. His posters belong to the tradition of American graphic design from the 1930s, drawing inspiration from the vibrant, stylized lines of earlier artists like Charles Montgomery Flagg, creator of the iconic 1917 "I Want You" Uncle Sam poster, and the realistic, emotive style of his contemporary, Norman Rockwell. In fact, in 1943—the same year León created his own Uncle Sam poster—Rockwell painted his renowned "Four Freedoms." Regardless of the specific influences, what is undeniable about this generation of artists and illustrators is their remarkable ability to evoke powerful emotional responses from viewers.

The question for contemporary artists who want to turn the tables of propaganda on the regime in turn, is not whether we can find good enough strategies to do so, nor whether we can adapt to the new media environment: along with the printed image on the streets, the new medium is the meme, the battlefield is social media, and the algorithm is our new pamphleteer.

The issues we face concern agility and clarity of message. In contemporary art practice we privilege the ambiguous and the nuanced symbol, not the propagandistic voice. I have often heard high-end curators critique artists who respond to urgent issues as opportunistic. Which ties with the other issue: the expectation that great art works are not journalistic, but rather iconic representations of the zeitgeist of a particular era.

But this is not a conventional era, and we can’t concern ourselves with nonsense questions of what is a more strategic or advantageous approach, nor can we waste our time worrying about the more intelligent response might be. We need to be clear, among other things, that 1) we are operating now under an entirely different set of circumstances; 2) we find ourselves in a completely different rhythm of public debate that has nothing to do with the one followed by museum and biennial calendars; 3) we urgently have to communicate beyond the readership of Artforum; and 4) we need to shed the intellectual affect and what in politics is described as “consultant language”. Obama speechwriter Ben Rhodes, in discussing the trouble that Democrats are currently having in connecting with voters, points out that this is what is killing the party right now: “if you do not sound like a human, you’re not going to be effective as a messenger.”

I was working at the Guggenheim in 2001 when legendary art historian and curator Robert Rosenblum organized a retrospective of Norman Rockwell. Rosenblum, always keen to break canonical dogma and provoke the status quo, thought that Rockwell deserved a place in American art, and this exhibition was a provocation to the purists. If Rosenblum didn’t succeed in elevating Rockwell to the level of the abex painters, he drove home the point that this kind of work spoke very differently, uniquely, and authentically, to the American experience. In an interview with PBS, Robert said:

Norman Rockwell stood for absolutely everything that modern art was against in the first place. It had to do with mirror-like realism. I mean, one of the marvels of Norman Rockwell’s art, which at the time was not thought to be a marvel, was how you could count every hair on thehead of this grand old man in the foreground or look at the mirror in the picture, which really had a reflection, like a real mirror, et cetera. So that was that, because the whole point of modern art was not to be a mirror image of the things we see, but something else, an abstraction of it or an interpretation of it. And then another thing that made him absolutely the enemy with Capital E was the fact that he told stories. This was another thing we learnedabout modern art. Modern art was not supposed to tell stories. It was not supposed to be literature. It was supposed to be something pure and visual. It had to do with things that were aesthetic, things that were lofty, things that transcended the daily facts of life and pictures that told stories were absolutely on the bottom of the pecking order so that in every possible way, too much realism just mirrored truth. Too much storytelling and usually cute kind of storytelling. Norman Rockwell was out. And then, of course, the thing that made him the real enemy was that when the cause of modernism was still on fire, this was an elite point of view. This was the minority view. And you had to be very, very passionate and intelligent and trained in order to go to sanctuaries like the Museum of Modern Art. Whereas Mr. Rockwell was one of the most popular artists of the 20th century and every American loved him and there was absolutely no problem in drawing him. So that at that time, popularity almost meant that the artist was beyond the pale. He couldn’t be a good artist if he was liked by everybody who bought the Saturday Evening Post.

This is why I often turn my attention to my uncle León and his contemporaries, the commercial illustrators—those outside the modernist canon—who, despite their exclusion from the arbiters of high art captured the attention of millions. Their work delivered authentic, straightforward messages, executed with impeccable technique and clarity. While lacking the deep or intricate nuance that is the fodder for art interpretation, their images became ingrained in the national consciousness. Perhaps there’s something we can learn from them as we step into the fray, seeking to reclaim control over the images made by those who are trying to control us.